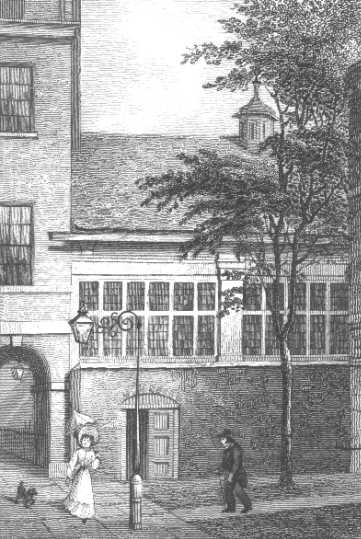

Owing to the largesse of an early market maker, Gresham College in Barnard's Inn, London, is the venue and sponsor of a 400 year-old series of public lectures. According to the original charter, all manner of subjects are to be covered, especially those that are of relevance to the City of London. And since every aspect of human life impinges on the City's sphere - finance and trade - every aspect of study is promoted and presented by the eight Professors of Gresham. So it is that one finds superbly explicated exegeses on astronomy, physics, commerce and finance, history, music, the arts, architecture and politics.

Owing to the largesse of an early market maker, Gresham College in Barnard's Inn, London, is the venue and sponsor of a 400 year-old series of public lectures. According to the original charter, all manner of subjects are to be covered, especially those that are of relevance to the City of London. And since every aspect of human life impinges on the City's sphere - finance and trade - every aspect of study is promoted and presented by the eight Professors of Gresham. So it is that one finds superbly explicated exegeses on astronomy, physics, commerce and finance, history, music, the arts, architecture and politics.

Many of the lectures are sponsored by the Mercers' Company, one of London's oldest livery companies. In the little hall of Barnard's Inn where the lectures are held is a wooden plaque with the names of the Masters of the Mercers. The first is that of an unfortunate man named Boncle in the 17th century, which serves to amuse those of us with a sophomoric sense of humour.

When Veena pointed me to the City of London Festival, a summer full of fun and intellectual heft, one of the first events that caught my eye was the lecture on the Last Mughal at Gresham College by William Dalrymple. I am a big fan of this man's writing - to be accurate, a bigger fan of his earlier writing than his later. But that's no fault of his. As his attention turned to the interplay between the British and the Indians, my own switched off, preferring the medieval ages to more modern times. Still, why not see the man in the flesh?

Arriving in the pouring rain at Barnard's Inn forty minutes ahead of the lecture, I am disappointed to be told by the ushers that the main hall is full, and that I would have to proceed to the basement to the 'overflow' room, to follow the lecture on a large screen. Damnation! I might as well download the lecture from the Gresham website and watch it at my leisure. Still, there's the possibility of meeting the author post-speech, so I descend into the bowels of the building and grab a likely chair.

The lecture starts promptly at seven. The host announces that there will be drinks and a book signing at the end, and urges us to stick around till then. Dalrymple, balding, bounds up to the lectern and apologises for looking like a call-centre employee. An elderly man sitting next to me starts to guffaw slowly. Previously I had encountered such laughs only in Wodehousian novels. A meaty, throaty "Haaaw-haaw," don't you know. Then Dalrymple goes full swing into the meat of his story, which is that of Bahadur Shah Zafar, and the stellar literary scene he created about him in Delhi while his kingdom shrank into the walls of the Red Fort. He speaks of the gradually changing attitudes of the British from humble supplicants to racially superior colonialists. He describes the ecumenism among the Hindus and the Muslims of India, and their steady polarisation over time. He puts up images of buildings in Delhi that no longer stand, razed by the British after the revolts of 1857. He displays pictures of snotty Scotsmen such as his ancestor-in-law, James Foster, whose dourness softened in the warmth of India, and who became more native than the natives themselves. And, of course, he mentions - as he always does in any narrative of North India - David Ochterlony, who was wont to parade around Delhi with his thirteen wives, each on a separate elephant.

The initial light humour darkens somewhat as Dalrymple launches into the Mutiny itself. Likening British attitudes of the time to American world-view of today, he excoriates the hate-mongering of the right-wing press then and now. He vigorously insults the likes of George Tenet (who claimed that the American takeover and control of Iraq would be a slam-dunk; the British had thought the same with their 100,000 mercenaries attempting to wrest control of Delhi back from the mutineers, and before the evening of the first day of the attack, 30,000 of them lay dead). He pooh-poohs Samuel Huntingdon ("Clash of Civilisations and all that nonsense," he says, pointing out that contemporary  life in India was ecumenical, a blend of faiths, and the madrassahs that are feared today were considered during the 19th century the equivalent of Oxbridge in the rigour of their studies and sweep of their coverage). And he criticises neo-cons such as Paul Wolfowitz, whose 18th century equivalent, Arthur Wellesley, despised both the mercantilist ideals of the East India Company, and the cheese-eating surrender monkeys who vied with the British for dominion over India, and was ambitious and destructive enough to want to seize overall power over the country.

life in India was ecumenical, a blend of faiths, and the madrassahs that are feared today were considered during the 19th century the equivalent of Oxbridge in the rigour of their studies and sweep of their coverage). And he criticises neo-cons such as Paul Wolfowitz, whose 18th century equivalent, Arthur Wellesley, despised both the mercantilist ideals of the East India Company, and the cheese-eating surrender monkeys who vied with the British for dominion over India, and was ambitious and destructive enough to want to seize overall power over the country.

At the end, Zafar, a man broken by the brutal slaughter of his sons, was demonised by the British and exiled to Burma. Delhi was crushed under the bitter heel of the victors. Dalrymple concludes his lecture with a moving verse by the last Mughal, an elegiac and deeply unhappy, but loving, poem to his wife.

After the lecture, the lucky public in the main hall streams out towards the drinks. One elderly Englishwoman is jostled by some brown-skinned individual, and she begins to scream imprecations. "The cheek!" she shouts in a gravelly screechy voice, "The impertinence! Why don't you go back to India?"

Now that is true irony, I think. Here is a woman who, having listened to an hour-and-a-half to a lecture on amity and harmony and the perils of racism, has learned nothing, and exemplifies precisely the quality of her forebears that ruined India.

"Welcome to England," says a locally brought up desi pal of mine when I tell him the tale. "At once sublime and nasty." How true.

3 comments:

She was probably disappointed in his lecture.

So she was telling him to go back to India? That would be irony indeed...

I am midway through the Last Mughal. Its amazing how the Mutiny era is brought alive flesh and blood and the events and characters made alive so Shakespeare-like without judgement. I got the feel as if persons involved are themselves caught up in the events despite themselves - they are helpless, and reacting to a period of extreme change. As for the lady in question, I guess some people never change.

Post a Comment