Peter Ackroyd, the prodigiously learned biographer of this great metropolis, is not known to suffer fools gladly. Indeed, shortly after his superlative book on London was published, he was asked what advice he had for visitors here.

"Leave," he replied.

Still, he thought nothing of presenting a visually appealing series of programmes on the river Thames for ITV. While unlike BBC's excellent iPlayer, ITV doesn't appear to have a repository of old shows for online or downloadable viewing, still, I would recommend to anyone with an interest in the times and tides of London to keep a close lookout for repeats, or beg a copy from a prescient pal.

What follows is a rather incomplete transcription of the first of the episodes of the series, which has its genesis in Ackroyd's paean to the river, Thames: Sacred River.

It is the shortest river in the world to have acquired such a famous history. The Amazon and the Mississippi cover almost 4000 miles, and the Yangtze almost 3500 miles. But none of them has arrested the attention of the world, of poets and novelists, of artists and historians, in the manner of the River Thames.

This is the story of the life and death of civilisations. This is the story of culture and geology shaping one another. It is the story of myth interwoven with history. The river embodies the history of the nation. From Greenwich to Windsor, from Lambeth to Oxford, from the Tower to the Abbey, from the City to the Court, from the Port of London to Runnymede, it has reflected the moving pageant of the ages. Its history is that of the Britons and the Romans, the Saxons and the Danes, and Normans, settlers somewhere along its banks.

Two places claim to be the source of the river Thames. One of them is at Seven Springs near Cheltenham. It has an ancient stone bulwark with an inscription in Latin: Hic Tuus O Tamesine Pater Septemgeminus Pons. Here, Father Thames, is your seventh source and spring. There's a small impediment to this claim, for the stream that issues from here has always been known as the Churn. The place with the better claim, although it doesn't look the part, is known as Thameshead. For most of the year, it appears as dry ground, but during times of heavy rain, the spring rises to the surface. It is here, five or six feet below the ground that the channel of the Thames begins. This will grow and grow, and by the time it reaches its mouth, its width will be five-and-a-half miles.

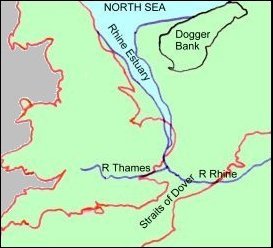

The River Thames emerged as an observable entity some 30 million years ago. At the time, Britain was connected to the continent via a land bridge where the North Sea now reigns. The Thames was a tributary then of a much larger river that flowed across Europe. The longest stretch of that river is now called the Rhine.

The River Thames emerged as an observable entity some 30 million years ago. At the time, Britain was connected to the continent via a land bridge where the North Sea now reigns. The Thames was a tributary then of a much larger river that flowed across Europe. The longest stretch of that river is now called the Rhine.

So the river is the oldest thing in London, containing shells, sedges and rushes that belong to prehistory. It created London. It brought it trade, and so lent it dignity and squalor, and brought wealth and misery to the city. London could never have existed without the Thames. So the history of the city is also the history of the river.

Gustave Milne, an archaeologist at the UCL, says that the river is London's longest archaeological site. Artifacts dating from the Neolithic period are often found. There are vestiges from the Bronze Age, and submerged forests, and every period of the city is represented all the way down to the shipyards of the Industrial Revolution.

When Britain ruled the world, the area between Tower Bridge and the Sea was where the shipyards were. From the 16th century onwards, most of London's ships were built here. Ships were broken up, repaired and rebuilt here; the carcases of old ships were recycled to establish solid platforms on which newer ships could be wrought.

For 1900 years from the earliest incarnation of London, the Thames was the principal highway in England. In the medieval period, castles and palaces and abbeys were built along its banks. It became the river of power. In the 16th century, it became the river of pomp and magnificence, a river of pageant and spectacle unifying the nation. That is why the Thames has been described as a museum of Englishness itself.

The Normans built the Tower of London as solemn icon of kingly power. In its earliest essence, it was the White Tower, and they moved heaven and earth to construct it: great barges bringing blocks of stone quarried in Caen. They built Bayard's Castle on the back, by Blackfriars. The Normans established the castle at Windsor, on a high gnarl of chalk, as another token of military pre-eminence.

The river has always been the provider of strength and sovereignty. There was an old fortress in the seventh century at Windsor, and Kingston-upon-Thames has provided the venue for the coronation of no less than seven Saxon kings. One sovereign, annoyed because London would not pay for some of his adventures, threatened to remove himself and his court to Winchester or to Oxford. The Lord Mayor of London replied,

The river has always been the provider of strength and sovereignty. There was an old fortress in the seventh century at Windsor, and Kingston-upon-Thames has provided the venue for the coronation of no less than seven Saxon kings. One sovereign, annoyed because London would not pay for some of his adventures, threatened to remove himself and his court to Winchester or to Oxford. The Lord Mayor of London replied,

Your Majesty may remove yourself, your court and your Parliament to wheresoever you wish. But the merchants of London have one great consolation: you cannot take the Thames with you.

The Thames was seen as a microcosm of the nation, with its past and present running mingled into each other. It was liquid history. If you look into it, you can see reflected the face of London, and the face of England itself. It is mild and moderate ... it is calm and resourceful... it is passionate without being fierce ... it is not flamboyantly impressive ... it is large without being too vast ... it eschews extremes ... it weaves its own course without artificial diversions or interventions ... it is useful for all manner of purposes ... it is a practical river.

On this historic river, everyone is equal. When you leave dry land, you leave the rules of the land. The water is the greatest of equalisers. It is well-known that water seeks an even level. But this is more than just a metaphor. Throughout its history it has been understood that the river is free for all people.

In the Magna Carta, sealed by the banks of the Thames, the great rivers of the English kingdom were granted to all men and women alike. In the 19th century, the Thames was declared a free and ancient highway, along which any Englishman or woman was allowed to travel without hindrance.

The Thames has always been considered a holy river, a vessel of peace that passeth all understanding. It is, in fact, a river of churches, many of whom were built by bridges and forts. There were often churches on the bridges, so that there was often a connection between worship and the crossing of the water. Their history often begins with the wooden constructions of Saxon origin, but almost all the churches in the Thames Valley had taken their present form by the 11th century. It is a remarkable story of continuity.

At Iffley near Oxford is the most perfect Norman church in England. Dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin, it is perched above the river. To visit the church now is to become aware of solemnity and old time. There is a palpable silence here, a perpetual harbouring of worship.

At Iffley near Oxford is the most perfect Norman church in England. Dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin, it is perched above the river. To visit the church now is to become aware of solemnity and old time. There is a palpable silence here, a perpetual harbouring of worship.

Reverend Andrew MacKearny, the vicar of Iffley says that there was almost certainly a Saxon church here, although nothing remains of it. Prior to that, it was a sacred site of some kind of pagan origin, connected to the fifteen-hundred-year old yew tree that stands on its grounds, predating any Christian worship in the land. There is a communion here between the river and the church and the grounds and the yew tree, a tangible sense of the sacred that has lasted for millennia. It is an extraordinary privilege, says the Reverend, to be a guardian of that spirituality.

The Thames is a sacred river. There were fifty churches and chapels along its banks dedicated to the Virgin Mary, who can truly be hailed as the Goddess of the Thames. It can be called Mary's River. Virgins were bathed in the Thames to make them fertile - one of the oldest myths of the river - so who better to bless the river than the Virgin herself?

The place where waters converge has always been sacred. At its core lies worship. These ancestral places were in use for many thousands of years. And if we do not understand the past associations of the river, then we will never understand the nature of its present in the modern world.

12 comments:

Great post.

loved it. thanks for kindling in me a new interest in a unique aspect of the history of Norman England.

could you suggest some more resources for the history of Anglo Saxon and Norman chruches built on the banks of the Thames?

meanwhile i'll try to get hold of the BBC series.

oh just realised it's an ITV series...

:)

OT, but your essay's up on BB.

Harkabir: thanks for stopping by. I'm not sure I know of any resources for Norman churches along the Thames, but this website has a lot of detail on sacred spots all over England. Let me know what you think of it.

SB: Thanks! I'll probably setup a backlink hither thither.

Hic Tuus O Tamesine Pater SeptemGeminus Fons

= Here O Father Thames is your sevenfold spring.

http://thames.me.uk/s02370.htm - Where Thames Smooth Waters Glide.

John Eade

Father Thames: thanks for the correction and the link!

I have been coveting Ackroyd's Thames book for months now. Sigh. Great post!

thanks fot the url. the sacred destinations of england website is nice but it's directory at best. what's missing are a timeline and internal linkages between the various religious sites. also there is no option to explore these sites in accordance with a theme such as a certain period, a ruling dynasty, a common feature of some of these sites etc.

none the less the material presented is top notch, all that's missing are the architectural plans :)

Aishwarya: thanks for stopping by and your comment. Indeed, in this instance, as I mentioned in the post, I can take no credit: it is essentially a transcription of Ackroyd's presentation. Regarding his book on the Thames, it is just as prodigiously researched and densely written as his biography of London, and needs to be read and re-read. Even then, it's a major information overload, albeit very pleasurably delivered :-)

Harkabir: the information available on the themes you seek is quite vast on the WWW, especially for European history. Once you find a thread, please be sure to post! I look forward to your writing.

How ancient is that Latin inscription? The word septemgeminus appears in a poem by Catullus, describing the Nile delta. I was taught that that was its only occurrence in ancient Latin literature, a hapax legomenon. Maybe Catullus coined it. It appears to be an adjective associated with septuplets - so meaning one of seven or sevenfold or seven-streamed.

Anon: you may be right - a search on Google reveals Catullus as the earliest cited user of the term. Statius in his Sylvae a century later uses 'septemgemino' with reference to Rome (seven hills and all that). Later on, Milton has used the word in Elegiarum.

The website that Father Thames mentions in his comment above has a reference by Paul Gedge to this inscription in 1949. As for the age of the sentence itself, I'm no classicist, so if you uncover any further detail about it, I'd be grateful if you would share it.

Who knows where to download XRumer 5.0 Palladium?

Help, please. All recommend this program to effectively advertise on the Internet, this is the best program!

Post a Comment