Although it had been planned a while ago, it was a good breather away from all the market turmoil to have cocktails and a guided tour at the National Gallery last week, under the aegis of Credit Suisse. It must be said that I had been looking forward more to the gallery than the drinks and canapés, and the evening was well worth the time.

While sundry clients of Credit Suisse milled about - they all seemed to know each other well - I lurked among the masterworks of Italian art. Several of Canaletto's razor sharp renditions of view of Venice were on display and I stopped to gawp at each one, wielding a nutmeg-laced lemonade in one hand and a flour-boxed-rabbit-pie in the other. I had hoped for some more participation from my own colleagues, who had also been invited, but they had all preferred to go to a bar near the office.

The guided tour was to begin at 7:30pm; it finally started about fifteen minutes later. RL, one of the gallery's experts in European art, said that she had received requests for several artworks and hoped we wouldn't mind beginning with John Constable's The Hay Wain (1821). The reason for this, she said, was that while it is now considered Britain's favourite British painting (at least, so say the listeners of Radio 4), in its own time it was scarcely appreciated by the contemporary public. Nobody in England wanted to have anything to do with it. Constable sent it to France, which was at the time going through a period of considerable Anglophonement. The bucolic beauty of Suffolk that he portrayed so well enthused such painters as Delacroix and Huet, but although the Hay Wain won a gold medal at the Paris Salon in 1824, nobody in France bought it either.

The guided tour was to begin at 7:30pm; it finally started about fifteen minutes later. RL, one of the gallery's experts in European art, said that she had received requests for several artworks and hoped we wouldn't mind beginning with John Constable's The Hay Wain (1821). The reason for this, she said, was that while it is now considered Britain's favourite British painting (at least, so say the listeners of Radio 4), in its own time it was scarcely appreciated by the contemporary public. Nobody in England wanted to have anything to do with it. Constable sent it to France, which was at the time going through a period of considerable Anglophonement. The bucolic beauty of Suffolk that he portrayed so well enthused such painters as Delacroix and Huet, but although the Hay Wain won a gold medal at the Paris Salon in 1824, nobody in France bought it either.

There is considerable artistic licence in the painting, of course, but much can be forgiven in a work of such optimism and beauty. The eponymous wain, or cart, in reality would have had much higher side walls to hold the hay in; the harnesses of the horses would scarcely have been such a rich red; the 'cottage' to the left in reality was a rather large and wealthy house (which stands, interestingly, to this day). Constable recalled his happy childhood in Suffolk in this painting - a sunny day, workers in the distant fields, clouds both white and grey. His critics accused him of splashiness and spottiness, but it is hard to say how either of these accusations could be labelled against the Hay Wain.

[Although our guide didn't mention this, I was reminded suddenly that a hundred and sixty or so years earlier, Peter Paul Rubens had executed the very similar An Autumn Landscape with a View of Het Steen in the Early Morning (1636). Again, there is a horse-cart, a stately house, a beautiful sky. Of course, there are no workers in the fields as in Constable's painting; instead, the lord of the manor promenades with his wife, while a nurse cradles a baby; there's a hunter in the foreground out to get some partridge in the early morning; the scattered woods in the distance are somewhat more unruly than the neatly organised fields of the Hay Wain. This painting is also in the National Gallery, and well worth a look; Constable admired this great canvas, and clearly was inspired by it.]

The next painting we stopped at was Paul Delaroche's The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833). Delaroche conformed to Joshua Reynold's diktat that the only useful art was which elevated the viewer morally, and to do so, must portray either heightened  nobility or heightened suffering. Jane Grey, the unfortunate teenage queen of England executed in the midst of the Catholic-Protestant struggle for the throne, is shown as noble, suffering quietly; her hair is undone; the entire painting is smooth with barely a brush mark; the light on her is numinous; even the executioner looks as though he wished he were elsewhere. Her rich robes have been cast aside and she is in her undergarments, but she does not protest, she submits to her fate. Delaroche, at the same time, is making a strong political statement - it is the Bourbon restoration in France and he is clearly a monarchist, for he shows the executioner in the anachronistic cap and shoulder ornament of the revolutionaries of fifty years before, who had murdered the then King and Queen of France. Delaroche preferred drama to historical fact, clearly evident in his placement of the execution of Jane Grey in the dungeons, and he ignores as well the fact that

nobility or heightened suffering. Jane Grey, the unfortunate teenage queen of England executed in the midst of the Catholic-Protestant struggle for the throne, is shown as noble, suffering quietly; her hair is undone; the entire painting is smooth with barely a brush mark; the light on her is numinous; even the executioner looks as though he wished he were elsewhere. Her rich robes have been cast aside and she is in her undergarments, but she does not protest, she submits to her fate. Delaroche, at the same time, is making a strong political statement - it is the Bourbon restoration in France and he is clearly a monarchist, for he shows the executioner in the anachronistic cap and shoulder ornament of the revolutionaries of fifty years before, who had murdered the then King and Queen of France. Delaroche preferred drama to historical fact, clearly evident in his placement of the execution of Jane Grey in the dungeons, and he ignores as well the fact that the queen's hair would have been tied back or shorn before her neck was put on the block.

the queen's hair would have been tied back or shorn before her neck was put on the block.

Although Jane Grey is shown in her underclothes, there is a sense of pathos that tugs at the heartstrings of the viewer. The sight, on the other hand, of the two women lounging by the River Seine in their undergarments in Courbet's Les Demoiselles au borde de la Seine (1857) caused outrage in critical circles. Clearly, these women were immodest! Prostitutes! Promenading in their pants! Debasing the morality of the public! Coubert maintained that the world needed to be shown as it was, not as it should be. "Show me an angel and I'll paint it!" he said. In a reworking of this painting he showed a man's hat on the boat, suggesting that both boat and women were hired out for the day. However, in Painting the Difference: Sex and Spectator in Modern Art, Charles Harrison says this is too glib a conclusion.

It is clear enough that the setting of the nearest woman just inside the threshold defined by the picture plane, the high horizon, and the steeply inclined ground plane all serve to imply a standing spectator who is assumed to be close to the women and looking down. Yet while one of the women looks into the distance with evident unconcern, the other appears to be laid out on the point of sleep. Her carefully detailed somnolent regard is far from being a look of enticement. The further implication of the picture, I think, is that the main event is over. However the actual spectator may respond to the depicted content, the imaginary spectator is now of no importance to the women. He is no longer even trade.

In Edouard Manet's The Execution of Maximilian (1867-8) was combined both the political commentary of Delaroche and Courbet's notion of painting the world as it was. Manet had hitherto been condemned as indifferent and detached from society, but with the display of this canvas, his engagement with the great matters of the day was made evident. Maximilian, brother of the Austrian Emperor, had been installed Emperor of Mexico by a French army, and then callously betrayed when the army was recalled by Napoleon III: Benito Juarez's republican army captured him and put him to death by firing squad in 1867. Manet, shocked by the perfidy of the French monarchy, stated what was obvious to him: Maximilian, for all practical purposes, had been murdered by the French. In his painting, therefore, he showed the firing squad in uniforms resembling those of the French infantry, and armed with French muskets. If Maximilian and the executioners were only victim of circumstances, Manet hinted, then the real villain was Napoleon III, whose treachery had led to this terrible consequence.

Manet painted three versions of this scene, and the one (in four pieces) we see at the National  Gallery is the second (the other two are in Boston and Mannheim). It is in four fragments - I don't recall who caused it to be cut up (perhaps even by Manet himself?) - saved by Degas, and reassembled into a canvas about as large as the original.

Gallery is the second (the other two are in Boston and Mannheim). It is in four fragments - I don't recall who caused it to be cut up (perhaps even by Manet himself?) - saved by Degas, and reassembled into a canvas about as large as the original.

From violence to sunshine: we stopped, next, at Vincent Van Gogh's iconic Sunflowers (1888). Painted during his days of optimism, to persuade Gauguin ('the new poet living here', who, Van Gogh said, 'was mad about my sunflowers') to tramp around the south of France with him, to paint and observe, this is one of four he executed, although he thought only two of them to be worthy of being hung up in Gauguin's room. (The National Gallery has one, and the other is in Munich.) Van Gogh used three new brilliant yellow dyes (among which was chrome) that had recently been concocted by chemists, and he showed the cycle of life with these flowers, from bud to full floral glory to wilting and drying and death. The naturalness of the sunflowers are a stark contrast to the flat and contour-less tabletop and vase, and as Erika Langmuir says, his signature, 'Vincent', becomes a naive blue decoration in the glaze of the Provençal terracotta jar.

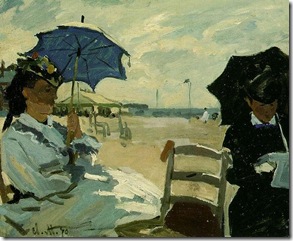

Constable, who had been much admired by his French successors, including the Impressionists, painted in his studio, referring to sketches he had made of the landscapes he saw. This lent a level of detachment to his final work: even if the scene depicted was as natural as he could make it, there was little immediacy. Claude Monet, on the other hand, painted the scene directly as he saw it, carrying the implements of his trade wherever he went. Thus we have, for example, his beautiful The Beach at Trouville (1870), executed almost spontaneously when he and his wife went there shortly after their marriage. The connection to scene is tangible, verily, for there are little grains of sand stuck to the canvas, blown thither by the wind as Monet looks on affectionately at Camille and her companion. Even that same wind is palpable in the painting, suggested by the flapping flag on the pole and the hazy rise of sand behind the seated figures.

Constable, who had been much admired by his French successors, including the Impressionists, painted in his studio, referring to sketches he had made of the landscapes he saw. This lent a level of detachment to his final work: even if the scene depicted was as natural as he could make it, there was little immediacy. Claude Monet, on the other hand, painted the scene directly as he saw it, carrying the implements of his trade wherever he went. Thus we have, for example, his beautiful The Beach at Trouville (1870), executed almost spontaneously when he and his wife went there shortly after their marriage. The connection to scene is tangible, verily, for there are little grains of sand stuck to the canvas, blown thither by the wind as Monet looks on affectionately at Camille and her companion. Even that same wind is palpable in the painting, suggested by the flapping flag on the pole and the hazy rise of sand behind the seated figures.

The last painting we studied before we wound up was Joseph Wright's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). Here we see scientific triumphalism as the new religion: the itinerant 'scientist', very like God the Father, demonstrates the necessity of air for life; the little girls are in tears seeing their pet choking for breath; their father attempts to comfort them by means of rationality; the grandfather on the right appears to contemplate the evanescence of life. The arrangement of the figures around the central scientist is reminiscent of medieval paintings of Christ surrounded by his acolytes, most of whom are rapt with ardour but some distracted, either by the sight of cherubim or angels showering Hosannas from on high. Derby was less interested in nature than in industry and science, and his work shows an obsession with technology. That spirit of inquiry led him to paint blast furnaces and mills and forges, tinged always with the play of light and subliminal suggestion of the supernatural. In this painting, there is the secondary light from the new moon, and, as Erika Langmuir points out, we see once again that in the 18th century, science and the occult were sometimes confused, and equally enthralling.

The last painting we studied before we wound up was Joseph Wright's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768). Here we see scientific triumphalism as the new religion: the itinerant 'scientist', very like God the Father, demonstrates the necessity of air for life; the little girls are in tears seeing their pet choking for breath; their father attempts to comfort them by means of rationality; the grandfather on the right appears to contemplate the evanescence of life. The arrangement of the figures around the central scientist is reminiscent of medieval paintings of Christ surrounded by his acolytes, most of whom are rapt with ardour but some distracted, either by the sight of cherubim or angels showering Hosannas from on high. Derby was less interested in nature than in industry and science, and his work shows an obsession with technology. That spirit of inquiry led him to paint blast furnaces and mills and forges, tinged always with the play of light and subliminal suggestion of the supernatural. In this painting, there is the secondary light from the new moon, and, as Erika Langmuir points out, we see once again that in the 18th century, science and the occult were sometimes confused, and equally enthralling.

Reference:

Erika Langmuir, The National Gallery Companion Guide, National Gallery Company Ltd, 2006.

4 comments:

did u see the michelangelo unfinished painting?

Hello there, and welcome. Which painting do you refer to? The evening I was there, we only toured the 1600-1900 area of the gallery, so didn't see any Michelangelos.

sorry - made a mistake, it was da vinci's virgin and the child that i meant.

There is indeed an unfinished Michelangelo at the National. It shows Christ being brought down from the Cross (The Deposition?) and features the characteristic muscular torso that is seen in all his portrayals of Christ (including The Last Judgement on the wall of the Sistine Chapel).

Post a Comment