Britain is a country that owes a great deal to its rail empire. For a century, the railways dominated the development of this country. This was a network that supported a global superpower. But today, the British Isles are home to ten thousand miles of disused lines, a silent grid of embankments, stations, and viaducts. For many, they have become the perfect platform for exploring the country on foot.

Along the banks of the river Spey, Scotland’s second longest river and one of its most famous, people come from far and wide to fish for salmon in its pure waters. And where the Fiddich meets the Spey is the heartland of one of the great drinks of the world. Walking along the Speyside railway line is therefore doubly special. Not only is it a beauteous trail, but it’s also a walk through the core of Scottish industry. We can find out here how the railway helped a small local product become an global icon.

By the mid-1800s, the river Spey already featured a number of distilleries along its course. As railway mania took hold in north-east Scotland, there was an obvious candidate for expansion. The cities of Aberdeen, Inverness and Perth were becoming slowly better connected. For the whisky industry, it was the arrival of the Strathspey railway in 1863 that really made the difference. New distilleries opened up along the tracks, which now offered great access to Edinburgh and Glasgow. This is where single malts could be blended and distributed across the UK and beyond.

The walk starts from the remains of the Craigellachie station, sticking firmly to this section of the Strathspey line. Even early in the day, there’s the prospect of trying out the local tipple. At the Craigellachie hotel, morning coffees, bar lunches, afternoon teas, fine dinners are offered, and, of course, over 550 single malts are available. But with 12 miles still to go, it’s probably best not to get distracted.

The route from Craigellachie to Ballindalloch is as follows: head south as straight as possible, while the river meanders its way through the valley, to the sizeable town of Aberlour, a name well-known to whisky aficionados; upriver, the tracks cross the river at the oldest distillery at Daluaine; pass the town of Carron, once a bustling community, now a quiet retreat in the shadow of the boarded up buildings of the old Imperial Distillery. Whisky hasn’t gone away from these parts: Knockando and Tamdhu are both alive and well, despite the ghostly nature of their stations. The Spey and the railway both turn south for a long straight run into Ballindalloch station, which gets the walker into the estates of the Macpherson-Grant family, who have been involved in the history of the whisky lands since the railway first opened. There is a final crossing of the river just before the station, and this is where the local populace would gather to drink long into the night as part of the Granary Ball.

No visit to Craigellachie is complete without inspecting the lovely iron bridge across the Spey built long before the railways by one Thomas Telford. When this bridge was built, Napoleon was still tearing up Europe, and Beethoven was still composing. Looking down it from above is like a view into the transport history of this country. Materials for the cast-iron bridge were brought by barge on the river, the great arterial ways of the age. Since 1812, Telford’s bridge, the railway, and the more recent road bridge, have all enjoyed their periods of dominance. And since the arrival of the railway, there has been no escaping the influence of whisky in Craigellachie. Surrounded by the Spey and the Fiddich, the town has two distilleries, and is the site of Scotland’s largest cooperage. 100,000 oak barrels are processed here every year, most of them acquired second-hand from the American bourbon industry. You can see them stacked up in pyramids, dozens of these neat structures on a flat field, with the glorious greenery stretching miles into the hills.

No visit to Craigellachie is complete without inspecting the lovely iron bridge across the Spey built long before the railways by one Thomas Telford. When this bridge was built, Napoleon was still tearing up Europe, and Beethoven was still composing. Looking down it from above is like a view into the transport history of this country. Materials for the cast-iron bridge were brought by barge on the river, the great arterial ways of the age. Since 1812, Telford’s bridge, the railway, and the more recent road bridge, have all enjoyed their periods of dominance. And since the arrival of the railway, there has been no escaping the influence of whisky in Craigellachie. Surrounded by the Spey and the Fiddich, the town has two distilleries, and is the site of Scotland’s largest cooperage. 100,000 oak barrels are processed here every year, most of them acquired second-hand from the American bourbon industry. You can see them stacked up in pyramids, dozens of these neat structures on a flat field, with the glorious greenery stretching miles into the hills.

Approaching the first great bend of the Spey, the walk takes you through an old, rare tunnel, one of only four in the entire Great North of Scotland network. You are right by the main road, but you can’t hear the traffic at all. On the other hand, the quiet murmur of the river is audible, calming and joyful. The railway was squeezed here, and the engineers had to cut through the stone and build a wall, which now acts as support for the road as well. The old railway then enters one of the familiar, long straight sections, with a vista of trees on either side that appears to go on and on. The undergrowth is dense, and little remains of the track. There’s only an occasional reminder of it to keep you company as you march along: mileposts that tell you how far you are from the local hub of Aberdeen.

The walk brings you to the outskirts of Aberlour, a town that balances its whisky credentials with another, quite different product – shortbread. Walkers are the producers of pure butter shortbread, founded on Aberlour’s main street by Joseph Walker; for over a hundred years, they have been expanding, and now are managed by the fourth generation of Walkers. One tradition has remained constant: it’s the local residents who get to test (and taste) any new biscuits.

The walk brings you to the outskirts of Aberlour, a town that balances its whisky credentials with another, quite different product – shortbread. Walkers are the producers of pure butter shortbread, founded on Aberlour’s main street by Joseph Walker; for over a hundred years, they have been expanding, and now are managed by the fourth generation of Walkers. One tradition has remained constant: it’s the local residents who get to test (and taste) any new biscuits.

What was once Aberlour station is now a visitor centre for the Speyside railway, and a tea-room. What is more interesting, though, is the Mash Tun, a pub that once was known as the Station Bar, and there’s a chance – just a little chance – that it may one day be called the Station Bar once more. The Mash Tun is named after a vessel used in the whisky-making process, quite apt, therefore, for a whisky bar in whisky country. It is run by Mark and Karen Braidwood, and they say that when the next train pulls into the platform nearby, they will be quick to rename it Station Bar.

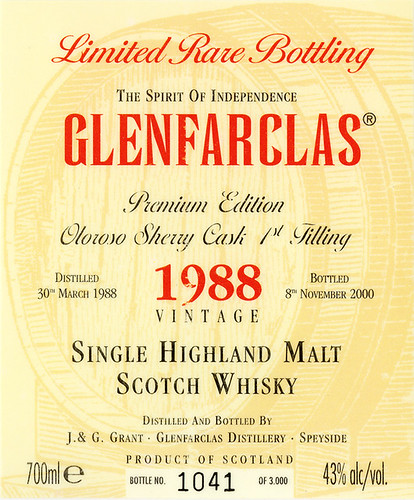

The Aberlour whisky is possibly the first whisky to attempt on this walk: done in sherry casks, very sweet, typical of the Speyside dram. It is smooth and strong, and you first try it neat to get its full flavour. It is a drink to sip and enjoy.

The Aberlour whisky is possibly the first whisky to attempt on this walk: done in sherry casks, very sweet, typical of the Speyside dram. It is smooth and strong, and you first try it neat to get its full flavour. It is a drink to sip and enjoy.

All whiskies are made in more or less the same way, but the little things such as the size and nature of the cask, the length of the aging, give each single-malt its distinction. Some people like to use the oaken cask, while others prefer used Chardonnay casks. The whisky needs to be in the cask for three years in Scotland for it to gain the appellation Scotch.

The Mash Tun is one of two comprehensive whisky bars in the world (the other is Bar Nemo in Tokyo), and this one boasts as well of the longest consecutive stock of whiskies, Glenfarclas, released from 1952 to 1994. The oldest, from 1952, would set you back £224 a dram.

Nemo in Tokyo), and this one boasts as well of the longest consecutive stock of whiskies, Glenfarclas, released from 1952 to 1994. The oldest, from 1952, would set you back £224 a dram.

An elegant footbridge enables you to cross the Spey as you walk out of Aberlour. Officially known as Victoria Bridge, the locals call it the Penny Brig, which was the toll you paid to use it. Alternatively, you can use the rather rickety suspension bridge across the Burn of Aberlour (the chief source of pure water for the local distilleries) that is dedicated to walkers. At one time it was a solid railway crossing, but now it rocks and moves underfoot, as you march purposefully on.

And once again you continue along a shaded path, greenery profuse, large tanks to your right, where the residues from the whisky-making are dealt with. Were they to dump the detritus into the Spey, its oxygen levels would drop, which wouldn’t be good news for the little trout and salmon that abound in it.

This treatment plant is for the Daluaine distillery, which has been in continuous operation since 1851. The railway arrived a dozen years later, and it became quickly obvious that the two industries could be of great use to each other. Daluaine received its own station years later.

Ian Peaty is an expert on the delicious and delicate interplay between iron and Scotch. He’s been writing a book on the subject, and visits the area often as part of his research. As he reveals, Daluaine Halt was built in 1933 for the whisky owners and their families. The large barrels and casks and industrial matter was brought up the quite steep hill in the distillery’s own puggy little railway. On the other side of the hill from the station, you can see a small distillery hidden in the glen.

The Scots gave an affectionate name ‘puggy’ to the most hardworking little locomotives that ran up and down the region. These were saddle-tank locomotives, meaning that the water tank sat on top. Until the best efforts of Dr Beeching in the 1960s, the puggy used to run all the way into the heart of the distillery. Today the work is done by a succession of lorries and tankers.

The Scots gave an affectionate name ‘puggy’ to the most hardworking little locomotives that ran up and down the region. These were saddle-tank locomotives, meaning that the water tank sat on top. Until the best efforts of Dr Beeching in the 1960s, the puggy used to run all the way into the heart of the distillery. Today the work is done by a succession of lorries and tankers.

A painting for Ian’s book reveals the third puggy, built about 1936, owned by the distillery owners, who bedecked it in their own livery. There used to be a shed where the locomotive would be serviced and kept overnight. An evocative picture it is, to be sure.

The idea for a puggy line was first mooted by the distillery owner William Mackenzie in the 1880s, but it took well over a decade for the line to be built. The final motivation for the line was provided by another distillery that was built by Mackenzie’s son: the line could now provide for both factories, the only complication being that they were on either side of the river. And so the puggy joined the mainline, with both sets of trains sharing the rather elegant Carron Bridge across the Spey (which was also a rare example of road and rail sharing the same infrastructure).

The river flows all the way down to the Morayshire coast, where a lot of the barley used in the whisky is grown.

Carron Bridge is a few hundred yards from the village of the same name, once a major stop on the Strathspey railway, and home to the Mackenzies’ second distillery. It is a much more substantial halt than the little one at Daluaine, but it is terribly run down. You notice that even the clock there has stopped ticking.

With the railway and the distillery at its heart, Carron village once bustled with life. The distillery was opened with considerable pomp in 1897, during Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee year, and was duly named Imperial. It had a high production level, which could only have been supported by the existence of the branch line that led right up to it. Today only the buildings remain. It’s become a silent distillery, and that’s how the people in the trade describe it. Carron itself has become an altogether different community. There’s something sad but beautiful about the silent distillery and its surroundings. The only lively part of the village now is the cottages, built by the distillery owner for his workers. Here and at other places along the railway, the locals could make a request halt of the trains. Quite literally, you could thumb a lift.

With the railway and the distillery at its heart, Carron village once bustled with life. The distillery was opened with considerable pomp in 1897, during Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee year, and was duly named Imperial. It had a high production level, which could only have been supported by the existence of the branch line that led right up to it. Today only the buildings remain. It’s become a silent distillery, and that’s how the people in the trade describe it. Carron itself has become an altogether different community. There’s something sad but beautiful about the silent distillery and its surroundings. The only lively part of the village now is the cottages, built by the distillery owner for his workers. Here and at other places along the railway, the locals could make a request halt of the trains. Quite literally, you could thumb a lift.

Strolling along a Beeching railway, you are suffused with thoughts of the past. Local stories, local people, a lost age still fondly recalled.

You mustn’t forget, though, that the Spey is still the centre of a global product. The nearby distilleries of Knockando and Tamdhu are an integral part of this global network. The former, beautifully housed, is owned by the same people as own Daluaine. A handful of multinationals dominate the industry, owning such labels as Johnny Walker, J & B, Grant’s and Bell’s. Few remain in private hands.

Despite the multinational presence, the Speyside is very quiet. You might expect the hubbub of articulated lorries and corporate throng, but look around – it is remarkably peaceful, well-managed, blending into the surrounding scape.

There is still a reverence for the past at these modern factories. The station at Tamdhu is beautifully preserved, and Knockando has a well-maintained Customs and Excise post, home to a figure who was very important to the industry, who logged the produce at each distillery, and ensure that not too much illegally disappeared when nobody was looking.

There is still a reverence for the past at these modern factories. The station at Tamdhu is beautifully preserved, and Knockando has a well-maintained Customs and Excise post, home to a figure who was very important to the industry, who logged the produce at each distillery, and ensure that not too much illegally disappeared when nobody was looking.

Three things shape your journey across the Speyside: the whisky industry, which depended so intimately on the river, and the railway, which followed the course of the Spey from the Scottish hills and valleys. Through it all, the Spey has maintained a totally unaffected character. This is Scotland’s fastest flowing river, winding a hundred miles, past the Cairngorms to its mouth at the Moray Firth. The railway, meanwhile, had to negotiate its major tributaries. There’s a viewing platform on one causeway across one such tributary, and it is quite a view, high, high above the tinkling stream.

The castle of Ballindalloch, built in the 16th century, is not visible from your trail, hidden as it is behind the dense canopy of trees. It is, however, the private residence of the Macpherson-Grants, one of clans of Scotland, and has been continuously occupied by that family since 1546. With five hundred years of history and 23000 acres of estates,they have clearly wielded considerable influence in the adjoining area. George Macpherson-Grant was one such luminary, forward-thinking to a fault, who established the nearby Cragganmore distillery. But the family was a prime mover in another domain as well. On their fields, cattle from Aberdeen were brought together with cattle from Angus. The beasts were well-fed with the discarded grain from the distillery, and a 150 years later, the herd is still intact, the original Aberdeen-Angus family.

The castle of Ballindalloch, built in the 16th century, is not visible from your trail, hidden as it is behind the dense canopy of trees. It is, however, the private residence of the Macpherson-Grants, one of clans of Scotland, and has been continuously occupied by that family since 1546. With five hundred years of history and 23000 acres of estates,they have clearly wielded considerable influence in the adjoining area. George Macpherson-Grant was one such luminary, forward-thinking to a fault, who established the nearby Cragganmore distillery. But the family was a prime mover in another domain as well. On their fields, cattle from Aberdeen were brought together with cattle from Angus. The beasts were well-fed with the discarded grain from the distillery, and a 150 years later, the herd is still intact, the original Aberdeen-Angus family.

Back on the other side of the river, there’s just a short walk to reach Ballindalloch village, and that’s where you tackle a final piece in this railway jigsaw. While the whisky trade made the railway unique, it was also vital to the local community, scattered across the sparsely populated area. One more river crossing brings you to your final destination, and this is a steel girder viaduct, 140 years old, and stern-looking, that leads to Ballindalloch station where you stop to learn about the arcane art of stealing whisky from its casks.

The Annual Granary Ball was the highpoint of life here in the days past. Up to a thousand fancy-dressed individuals from as far as Aberdeen would descend upon Ballindalloch on the specially laid on trains. In the 1920s and 30s, this was the place to be seen. Accounts suggest, however, that very little tipple was actually purchased at these balls. Instead, the locals would store their own supplies of liquor in the long grass outside the venue. They would have acquired these stores by means not entirely ethical. The staves of the casks that stored the whisky had rings on them, which the sneaky pilferer would remove, drill a little hole with a pocket gimlet, fill his pail with the gloried liquid, stick a wooden spike in the hole, cut off the excess, put back the ring, and neither the Excise man nor the owners would know that the barrel had ever been breached. Alternatively, they would carry long cylinders that they could dip into the barrels when nobody was looking, and cork the contents and slip the cylinder into their pockets – all the distillery boys would carry these containers, without any markings on them that might have inadvertently identified them.

The station closed in 1968, to the everlasting sadness of the Speyside villagers. The railways had brought their beloved industry to a global level, and whisky continues to be a vibrant produce with a great future. But the little things are missed the most – the school journeys on little trains, the puggies hauling material up and down the hills, a time of slow grace that is now gone.

[Based on Julia Bradbury’s eponymous Railway Walks, BBC Two.]

2 comments:

I was watching one of the Railway Walks series on BBC the other day and marvelled at the scenery, relatively unspoilt, that the tracks used to cut across.

Can't exactly remember where it was but I do recall that it was somewhere in Wales (might even be wrong about that). Would love to walk along one some day. Hmm...

CK: Go for it, man. Maybe start with the whisky trail, and carry a single malt along with you to pick you up when the Scots weather turns.

Post a Comment