On the eve of the First World War, the British Empire covered a quarter of the globe and governed 400 million people. When war broke out in 1914, Britain was overwhelmed by enthusiastic offers of support from every corner of the Empire, from the so-called White Dominions and the predominantly non-White Colonies. All wanted to prove their loyalty to the Empire.

At the outbreak of war, Mahatma Gandhi said of Indians: ‘If we desire its privileges, we should desire the responsibilities of membership of this great Empire.’ The Prime Minister of Canada was unequivocal: ‘When Britain is at war, Canada is at war. There’s no difference at all.’

The 150,000-strong Indian Army was huge, professional and available for immediate deployment, and it was keen to prove itself. However, there was initial resistance within the British establishment to the use of colonial soldiers in anything but a supporting role. The problem was that German forces on the continent outnumbered the British Expeditionary Force by something like ten-to-one. So the War Office had no real choice but to deploy the Indian Army, thus breaking the bizarre, unspoken gentlemen’s agreement on both sides to to have only White troops fighting in a European conflict. The Viceroy of India, Lord Harding, was gratified that the British authorities pragmatically dropped these objections, as he had suggested. He wrote to the Colonial Office in London:

September the 3rd, 1914.

I am now perfectly delighted at the idea of all our troops going to Europe. It has produced the best possible effect in India, for they feel now that the stigma of a colour bar has been removed and that our troops are in a position of equality with European troops, according to the standard of the civilised world.

As his grandson, Jaiman Singh Johal says, because he was educated, he rose up to the rank of Subedar, above the ranks of the Sikhs and just below that of the white officers.

This is September 26th. The march through Marseilles was one of great enthusiasm. Most enthusiastic reception extended to regiment throughout the journey. Baskets of fruits etc pressed on the men on every possible occasion.

We know a fair amount about what the Indian soldiers thought themselves because military censors monitored and recorded their letters. But when the troops first arrived in France, they can’t have had much to censor, and the letters are positively gushing. As an example, here is one from a Sikh (the letters were sorted by religion) went like this:

If you were to see the conditions of life here you would be astounded. What can be done? The man whom God wishes to punish is born in India.

Like all new troops on the Western front, Manta Singh and his regiment were unprepared for the dank trenches and unrelenting terror of industrialised warfare. Once they got to the front, the letters became less enthusiastic.

For God’s sake, don’t come, don’t come, don’t come to this war in Europe…

Tell my brother not to enlist. If you have any relatives, my advice is don’t let them enlist…

Cannons, machine guns, rifles and bombs are going day and night, just like the rains of the month of July and August…

Those who’ve escaped so far are like the few grains uncooked in a pot.

Unsurprisingly, the last one has a big red line down the side.

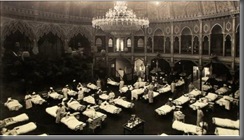

In just three days of fighting, the Indian forces had suffered more than 4000 casualties. Manta Singh and his wounded comrades were shipped from the front to hospital in England. And where could be more appropriate for an Indian soldier of the British Empire to recover than in Brighton’s Royal Pavilion, modelled on an Indian palace. At King George V’s suggestion, the city of Brighton had offered the Royal Pavilion for use as a hospital for the wounded of the Indian Army.

The wounded soldiers wrote home with their impressions.

We are in England. It’s a very fine country. The inhabitants are very amiable and very kind to us, so much so that our own people couldn’t be as much so. The food and the clothes and the buildings are very fine. Everything is such as one would not even see it in a dream. One should regard it as fairyland.

Another wounded Sikh wrote:

Do not be anxious about me. We’re very well looked after. Our hospital is in the place where the King used to have a throne. Men in hospital are tended like flowers, and the King and Queen sometime come to visit them.

Manta Singh had one, or possibly both his legs amputated. And then he died. His body was taken to the South Downs, one of 53 Sikh and Hindu soldiers who, having given their for King and Empire, were cremated in the open air, here, according to their beliefs. A monument to them, called the Chattri, stands on the very spot where the cremations took place. This was a remarkable act of what we would call cultural sensitivity on behalf of the British Army. Open-air cremations were illegal, and remain so to this day. But on this occasion, they were allowed.

An annual memorial service is organised by Brighton locals and Indian ex-servicemen. Captain Henderson, whose life Manta Singh had saved, survived the war. He, a professional soldier, had won the Sword of Honour at Sandhurst in 1911, and later sent out to India to join the 2nd 11th Sikhs, where Manta Singh was also serving. The regimental and family association endured into the next generation. There is a photograph of the sons of these two men standing next to each other, taken sometime in 1937.

Manta Singh’s experience coming so early in the war was a remarkably positive example of the Edwardian Empire working together. Years after the end of Empire, we may find it surprising.

But such loyalty and mutual respect was not unusual then.

[Text from Ian Hislop’s Not Forgotten, shown recently on Channel 4.]

3 comments:

Thanks for making this bit of history available. There is definately a lack of details about

the role of Indain soldiers in genral and Sikh soldiers in particular. I heard some stories from my pateranl grand father subedar Nihal Singh who was in Europe during this war. Jagdish S. Grewal, Damascus, Oregon, US

wonderful...this kinda reinforces what Dalrymple had been maintaining about the pre-1857 Empire being more humainstic. The Army offered the illiterate peasants and agriculturists employment, good moolah and social elevation. Became a status symbol and backward castes like the Jats were soon to emerge as rich landowners. This attraction to army remains. Just a month back, the local daily reported how in Ludhiana teh army recruitment drive turned up thousands of youth, most of whom had to be shooed off after they proved to many for the minimal requirements.

Im only a kid but all this information is incredible, and there isnt much of this kind of text anywhere on the internet.

Post a Comment