The part-time foodie recognises after a little bit of thought that the best way to learn about what our ancestors ate is to study their art. Not only secular but also sacred art throws considerable light on the food habits of times gone by. To look at a masterpiece such as the Last Supper is not only to connect with the spiritual sublime but also to salivate over the sumptuous repasts of the past. In Oliver Peyton’s neat little series of TV programmes entitled Eating Art, the episode dealing with the search for the culinary history of the Last Supper is, for me, the most compelling. It is fair to say that the meanings in the depictions of the Lord’s last meal are quite a bit more subtle than one expects from a work of sacred art. That is to say, the Biblical meanings are well-known, but the aspects of food on the table have rarely been mentioned.

Peyton starts in Ravenna where one finds the earliest artistic depiction of Judas’s betrayal of Christ. In the basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo is a sixth century fresco high up on the right wall, so high up that it can scarcely be studied without a good pair of binoculars.  In this marvellous exemplar of Byzantine mosaic work, there’s fish but no wine on the table. The fish are presented in the middle of the table – two large ones on a plate, mouths agape, eyes beady.

In this marvellous exemplar of Byzantine mosaic work, there’s fish but no wine on the table. The fish are presented in the middle of the table – two large ones on a plate, mouths agape, eyes beady.

In accordance with Roman customs, the Apostles, instead of being seated, are gathered around a triclinium, semi-circular in form, on which are two fishes and a few loaves of bread. Christ is seated on the left, in the place of honour, whilst Judas sits on the far right.

Some scholars maintain that the presence of fish rather than the Paschal Lamb is a representation of the 'Meal of the Pure' celebrated by the Jews on the Friday evening, a practice which spread to the Arians who similarly believed that Jesus himself had eaten thus before the Passion. (from here)

All we learn from this earliest artwork is that fish was eaten at the Last Supper. But if we continue to the Trentino region of Italy, we can see in a series of little churches a further evolution and embellishment of the Christian legend. These are 16th century frescoes that tell a very different story. A culinary historian named Carolin Young has investigated that story, and this is what she found.

In the Chiesetta Sant’Antonio Abate in Pelugo, a lovely little church ensconced in a terrain of mountainous beauty, is the first of the ‘peasant’ Last Suppers. Here is an abundance of food, lavishly illustrating the appetites of the apostles. There’s fish and crayfish and upside-down brioches in this painting, one of hundreds done by a prodigious family known as the Baschenis who painted the same scene over and over again all over the region. Carolin Young believes that the food was where the Baschenis could really let their imaginations run riot – the Church told them only how to structure the spiritual and hierarchical aspects of the apostles and Jesus. And so the content of the food depicted changed from town to town, almost as though each town was showing off its local delicacies and specialties. Pelugo’s specialty is crayfish, which is an idiosyncrasy, as it is not really kosher. Three of the four gospels tell us that the Last Supper took place on the first night of the Passover; having crayfish on such a holy occasion almost doubles the blasphemy. But Pelugo is situated on the banks of a river, and the crayfish was abundant in the river; in non-riparian towns, of course, we wouldn’t see this beastie in their paintings.

(The example in Pelugo is by Cristoforo the First; but as I am unable to find an image of that fresco, I show here a similar one from the church of Santo Stefano in Carisolo; this one, complete with crayfish, is by Antonio Baschenis.) Interestingly, the style of the bread also changes from town to town. It remains the sacrament, the body of the Christ, but it is always a local bread. Wine, too, appears all around; in some towns, it is red, in others, it is white, and in yet others, it is a mix of the two.

There’s also a pig! I guess the Pelugoans figured that if they might as well be in for a pound if they were in for a penny: the pig is almost unspeakably blasphemous in such a context, much more so than the crayfish. But of course your typical Christian in the Middle Ages, as anti-Semitic as can be imagined, didn’t think of Jesus as a Jew, and so the strictures of keeping kosher no longer even occurred to him.

What’s a good place to try out the centuries-old cuisine of the region? Peyton heads to the Auberge Mezzo Soldo, a Michelin-starred eatery in Spiazzo, to try out a traditional recipe of dumplings. While the usual ingredients of herbs, flour, fresh bread-crumbs and eggs, onions and garlic and butter, all bound by milk and cooked in water, are all very simple, the local sausage chopped and added in provides the strongest flavour. In contrast to the dumplings of other parts of Italy, where there might be at most three ingredients and considerably smaller, the Spiazzan offering is far richer and bigger.

In Castello Tesino is the 15th century Chiesa Sant’Ippolito, an older church than the one in Pelugo, but also adorned by the art of the itinerant Baschenis clan. Here the food depicted in the fresco of the Last Supper is fairly different from the Pelugoan fresco. The crayfish are absent. The diners are sharing plates, unlike in Pelugo – a remarkable pointer to the evolution of table ritual towards individual place settings. Here also there are examples of different wines, both white and red, specialties of the region. And here we have the classical lamb in a platter, a symbol of Christ obviously, a traditional Easter preparation. Carolin believes that the pig in Pelugo was an artistic licence; after all, there was a precedent of a pig in the Last Supper in Duccio’s work (shown below) in the 14th century, which predated even the traditional depiction at Castello Tesino.

By the 16th century, artists in Venice decided that spiritual significance was passé. The meal was placed centre-stage. A brilliant example of the new oeuvre is to be found in the Chiesa di San Giorgio Maggiore, a Palladian masterpiece in La Serenissima. In 1594, Tintoretto created his Last Supper, colour and mood that comes as an explosion after the frugality of the Trentino frescoes. A veritable banquet is placed on the groaning table. There is a drama of movement and action of the people around the food, all tightly wound and controlled in the new medium of oil-paint on canvas, which was becoming the medium of choice in Venice at the time.

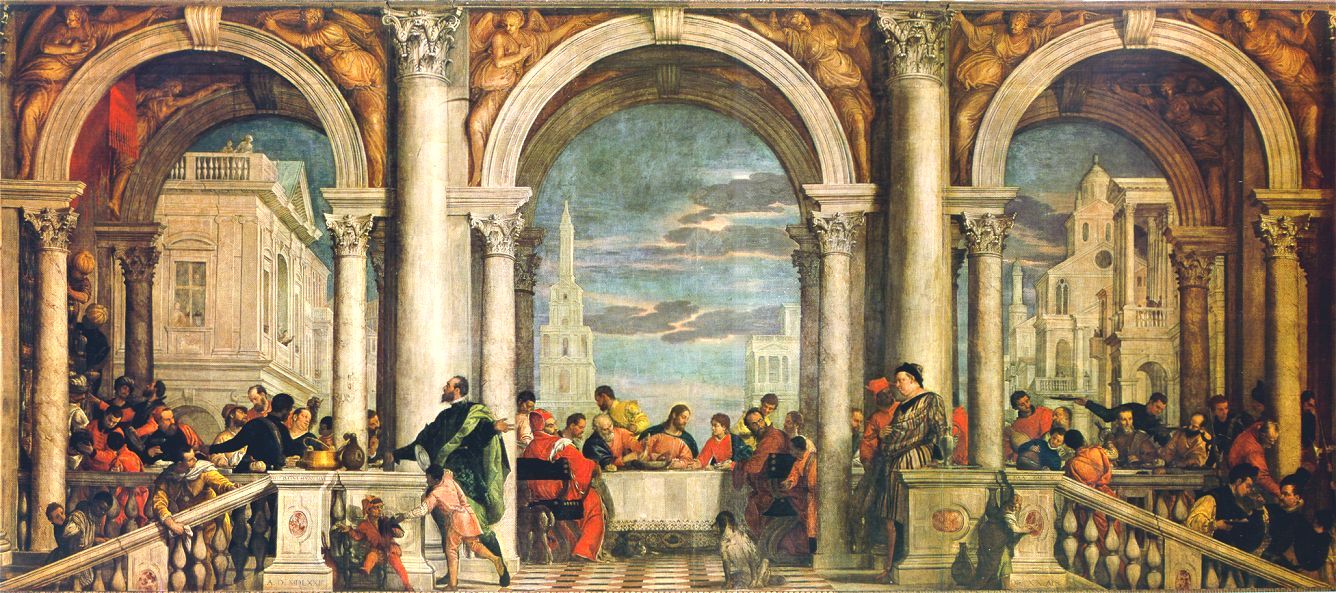

Another Venetian example of the Last Supper is Veronese’s 1573 painting, now found in the Gallerie dell’Accademia. This Last Supper very nearly landed him in prison. It is an enormous canvas, one of the largest of the 16th century, occupying a whole wall in the Gallerie. This is such a long way from that mosaic in Ravenna, or the rustic simplicities of the frescoes in Trentino. Commissioned for a convent, this is not so much a meal for Christ and his followers as a party, servants liberally pouring out wine, the table absolutely straining under all the food. The painting included cats and dogs, blackamoors, pagan revels almost, and even – God forbid - German soldiers! It was considered a religious insult, and Veronese was hauled up before the Inquisition. His defence was a stoic articulation of his right to paint what he saw and what he felt, perhaps not a line that the Catholic Church would easily swallow. He was allowed to go free but the painting was renamed Feast in the House of Levi. Who is to say if the notoriety helped or hindered Veronese’s career? It is clear, however, that he continued to flourish as an artist.

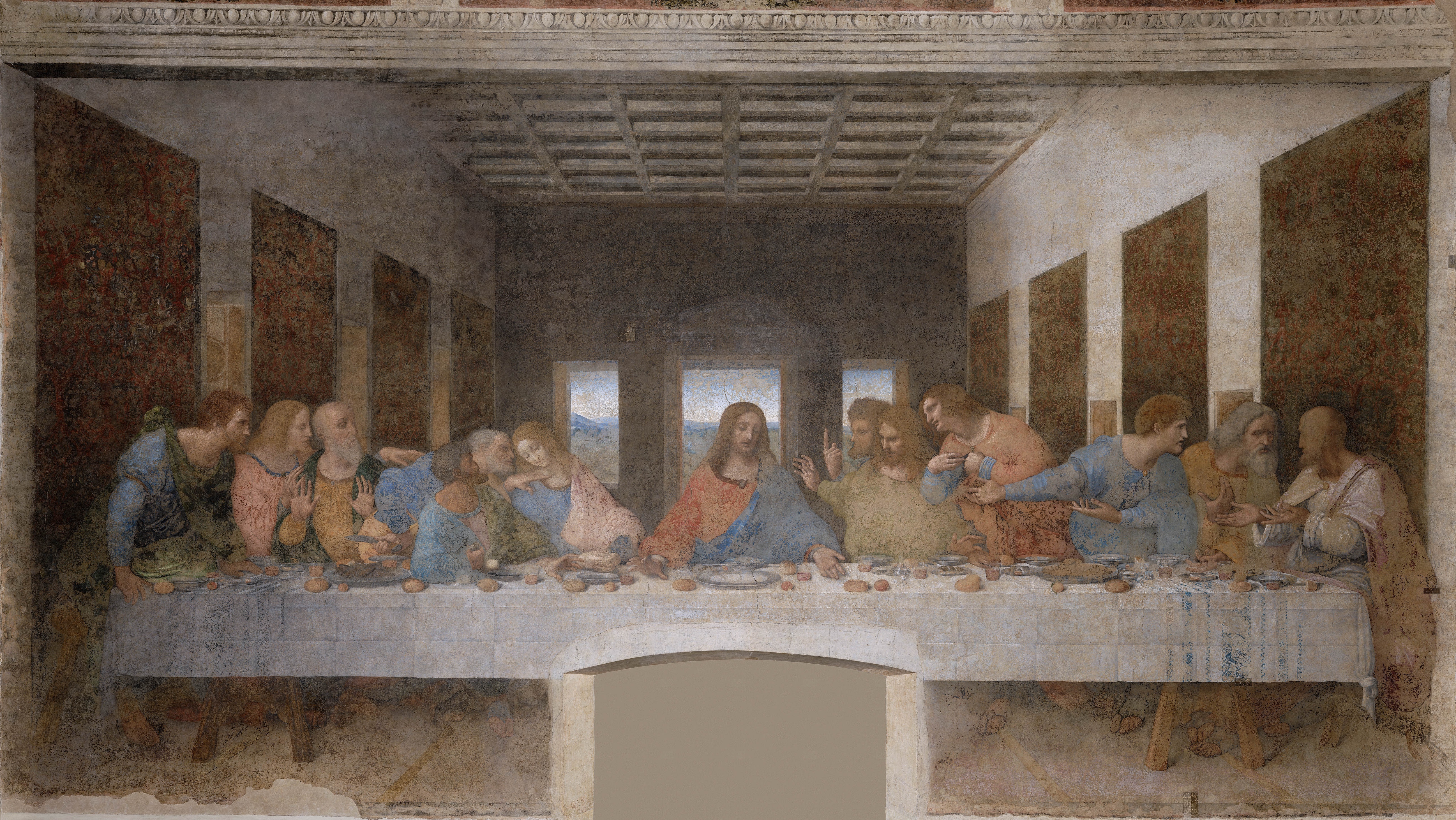

All roads in the story of the Lord’s Last Supper lead to Milan, where Leonardo da Vinci’s culinary masterpiece resides in the Santa Maria delle Grazie. The world may be persuaded that this was how Jesus’s final meal appeared, so famous is the painting and so sunk is it in the public consciousness. But Leonardo painted it to suit his own needs. It was commissioned for the refectory in this monastery, and he wanted the monks to feel part of the Last Supper, and so he placed all the disciples of Christ facing forward into the room. Jesus was hardly a man to surround himself in luxury, but the painting aims to display the richness of the food on offer and the grandeur of the dining hall. Wines and fish abound in a scene of splendid conviviality; it is certainly not a scene of poverty. There is drama in buckets, though – Jesus announces to his followers that one of them would betray him before that night was out, and Judas reaches for a bread near his hand.

From a culinary perspective, however, we see once again artistic licence. On the right hand side are oranges and eels; Leonardo puts them in because they were in fashion at the time. They were his equivalent of today’s Caesar salad.

More egregious, of course, is the doorway at the bottom of the painting. Apparently when Napoleon parked himself in this monastery, his flunkies who wanted to get to the kitchen (located behind the wall of the painting) decided to cut open the wall, and thereby marred what one of the greatest works of art in history.

***********

Oliver Peyton runs the National Café at the National Gallery in London, and he arranges his own Last Supper menu for some of his foody cronies. Here’s a look at part of the menu, which was accompanied by wine from the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon:

Smoked Eel with Pomegranate and Bitter Leaf Salad

Salt Baked Wild Sea Bass

Roast Leg of Rhug Estate Saltmarsh Lamb with Mixed Dried Fruit and Nuts

Cous Cous

Braised Chick Peas and Butter Beans

2 comments:

rumor has it that the last supper table was kept at the aya sofia in Istanbul..

I won't be surprised if that's another one of those relics like 'the head of john the baptist as a young boy'.

Post a Comment