What do you know, it’s that time of the month anew when birds chirp and the minds of bloggers turn to things festive and carnival-like. And so here we have the 35th instalment of the popular carnival of science. It promises to be a beaut. (Is it a beaut or is it a beaut? I’d say it is a beaut.)

History of Science

The first documented automaton is a flying dove from Greece in the 5th century BC. That knowledge transmitted itself subsequently to the Arab world. Medievalists.net have a short explanation.

If you were setting out to write a book about science and how it began, how and where would you begin? The question exercised Patricia Fara, who discusses it at Soapbox Science in Science: A Four Thousand Year History.

If you were setting out to write a book about science and how it began, how and where would you begin? The question exercised Patricia Fara, who discusses it at Soapbox Science in Science: A Four Thousand Year History.

|

| Down House (photo by Mario Modesto) |

Continuing the vicarious pleasures of armchair travel, check out Urban Ramblings, a post by Rupert Baker on the Royal Society’s connections with London at the History of Science Centre’s blog.

The teaching of evolution in the USA has long been a cauldron of political and religious trouble. In Political Descent, Piers Hale talks about the Scopes trial and other legal ramifications of what, essentially, should be a scientific issue.

Continuing on the theme of evolution, Asa Gray was Darwin’s supporter in America just as Thomas Huxley was in England. In Wired Science, David Dobbs recounts the story of Gray’s debates with Louis Agassiz that led to the respectability of evolutionary theory in the US. And – as a bonus – you can even read Gray’s review of the Origin of Species in the Atlantic Magazine.

Still on the topic of evolution, Dispersal of Darwin has a video charting the image of Charles Darwin over the years.

After Newton and Leibniz, a new rational philosophy took over the world of science, and people began to deride their predecessors (such as Athanasius Kircher) as scientific incompetents. BOOKTRYST has an article about a 1715 book that poked fun at Kircher and his fellows.

In the 1870s, the Dutch government decided to blow a ton of money on improving their scientific infrastructure, and assigned a million and a half guilders to Leiden University for, among other things, a new natural history museum. Where is that museum now? Collect and Connect explores.

Earth Sciences

In the Great War, the Austro-Hungarians created a special force called Kriegsgeologen, tasked with the use of geology for war. History of Geology describes them in War Geology.

Highly Allochthonous discusses whether large temblors beget more large temblors in The Many Faces of Earthquake Triggering.

Still on the topic of evolution, Dispersal of Darwin has a video charting the image of Charles Darwin over the years.

After Newton and Leibniz, a new rational philosophy took over the world of science, and people began to deride their predecessors (such as Athanasius Kircher) as scientific incompetents. BOOKTRYST has an article about a 1715 book that poked fun at Kircher and his fellows.

In the 1870s, the Dutch government decided to blow a ton of money on improving their scientific infrastructure, and assigned a million and a half guilders to Leiden University for, among other things, a new natural history museum. Where is that museum now? Collect and Connect explores.

Earth Sciences

In the Great War, the Austro-Hungarians created a special force called Kriegsgeologen, tasked with the use of geology for war. History of Geology describes them in War Geology.

Highly Allochthonous discusses whether large temblors beget more large temblors in The Many Faces of Earthquake Triggering.

Mathematics and Computing

The Osborne Company produced the first laptop computer way back in 1981. Have you ever heard of it? How to be a Retronaut tells you all about it.

Ravi Kannan recently won the 2011 Knuth prize for outstanding contributions to the foundations of computer science. Dick Lipton celebrates the achievement and discusses some of Kannan’s work at Gödel’s Lost Letter and P=NP

Physics

James Maxwell is the genius extraordinaire responsible for the first great unifying theory of physics. 150 years ago, he published the first of four papers that comprised his tour de force. The Economist’s Babbage blog tells the story.

If you are interested in the early scientific history of fission, you can do no better than to read the review by Louis Turner; Ptak Science Books discusses it.

Whipple Library has an article about the Nernst lamp, an innovative light source brighter than filament lamps and not requiring the use of vacuum.

| Pyro Optical Pyrometer |

There was a young lady named Fisk Whose fencing was exceedingly brisk So fast was her action That the FitzGerald contraction Reduced her rapier to a disk.

FitzGerald who? Skulls in the Stars talks about one of the first explainers of the famous Michelson-Morley experiments.

Astronomy and Space

In 1572, an English member of Parliament speculated - for the first time - on why (if the universe were infinite) the night sky was not fully lit up with stars in every line of sight. Jost A Mon (in other words, me) tells the story.

Einstein’s general theory of relativity predicts that light is bent as it passes near a gravitating object. What cosmological discoveries have been made by using this property of space? 365 Days of Astronomy has a nifty little podcast.

| The Earth and Moon as seen from Mercury (for some cosmononplusation; credit NASA) |

Chemistry

Abiotic genesis of life’s building blocks, anyone? The famous Miller and Urey experiments of the 1950s resulted in amino acids when a gloop of simple chemicals were subjected to electricity. Recent analysis of the vials left by Miller reveals that hydrogen sulphide in that primordial soup would have been even more efficacious. Life, Unbounded has the story.

|

| Lavoisier and Paulze by Jacques-Louis David |

Medicine and Pharmacology

If you have a pain in your spleen (and how would you know it was your spleen aching?), you can do no better than to follow Nicholas Culpepper’s advice from the 17th century, as Barbara blogs in 17th Century American Woman.

The lovely Res Obscura blog has excerpts and illustrations from a 1690 pharmacopoeia published in London. Check out The Treasury of Drugs Unlock’d.

The lovely Res Obscura blog has excerpts and illustrations from a 1690 pharmacopoeia published in London. Check out The Treasury of Drugs Unlock’d.

In medieval Europe, alchemy combined with medicine to produce a potent drug called Precipitato to restore the human body to its pristine natural state. It was so toxic that it required the most delicate handling. Read about it at William Eamon, Professor of Secrets.

| Not that kind of Chirurgeon |

Shortly after Dr Hahnemann published a paper in the British Medical Journal in 1859 on his new ‘discipline’ of homoeopathy, a Glasgow doctor named William Gairdner issued an exacting and trenchant critique. Memoirs of a Defective Brain has the story.

Smells Like Science has the story of Ether and the Discovery of Anesthesia.

And, in the vein of anesthesia, Providentia provides the details on The Chloroform Man.

Life Sciences

In the 16th century, people believed that there were fundamentally no differences in male and female genitalia, one being a mirror image of the other. Mirabile Visu talks about this gender inversion.

In 1733, two Swedish workmen reported finding a dull but live frog inside a boulder they had just cut open. Over the centuries, there have been other reports of immured yet live creatures found. Hoax or not? The History of Geology investigates in Toad in a Hole.

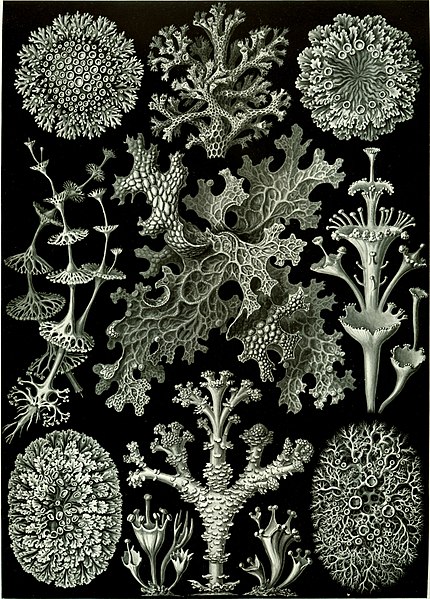

Ptak Science Books has a piece on Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904), a compendium of staggeringly lovely lifeforms found in nature.

Speaking of staggeringly lovely, have you seen BibliOdyssey's article on the Flora Sinensis, the first Western book (1656) to document the sub-tropical flora of China?

In 1733, two Swedish workmen reported finding a dull but live frog inside a boulder they had just cut open. Over the centuries, there have been other reports of immured yet live creatures found. Hoax or not? The History of Geology investigates in Toad in a Hole.

|

| Lichens from Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur (1904) |

Speaking of staggeringly lovely, have you seen BibliOdyssey's article on the Flora Sinensis, the first Western book (1656) to document the sub-tropical flora of China?

Why do people still insist that apes are not monkeys? It’s all down to an old taxonomy that is today quite obsolete, says PaoloV at Zygoma.

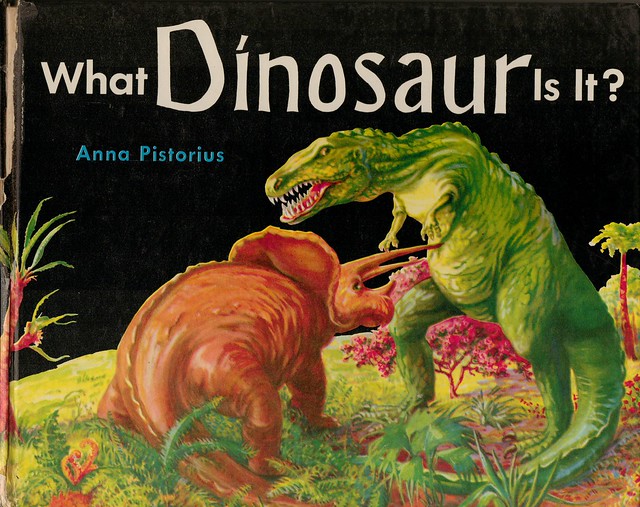

In the 1950s, Anna Pistorius created an illustrated book of dinosaurs for kids. Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs has some lovely scans and explanations from it.

In the 1950s, Anna Pistorius created an illustrated book of dinosaurs for kids. Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs has some lovely scans and explanations from it.

Kristina Killgrove, a biological anthropologist at UNC Chapel Hill, recounts the story of the ill-fated Tudor ship Mary Rose and describes isotopic studies aimed to determine the origins of its sailors in Powered by Osteons.

[And that’s it for May 2011, folks! Thanks to all those who submitted articles (and especially to Thony C., indefatigable as ever, for finding fascinating tidbits in the scientific blogosphere). I hope this encourages you to write up your own pieces on science and its history and philosophy. Do consider submitting your blog article to the next edition of the giant's shoulders. You can use the carnival submission form. Past posts and future hosts can be found on the blog carnival index page.]

3 comments:

Hi,

I didn't cover it in my post, but the circumstances behind the publication of this article is a complicated story in of itself. Hahnemann had been dead for a while before this publication. I know that Gairdner at some point wrote a review of historic medical discoveries, and their practitioners.

In this book, he characterised Hahnemann as a charlatan.

As a result of this, a homeopathic practitioner by the name of William Henderson published a 28 page diatribe against Gairdner.

The article is a response to that diatribe. In it, Gairdner presents the evidence behind his initial assertions in his book, and also why homeopathic practitioners will ignore them.

Samuel Hahnemann had passed away a decade before this article was published.

DB: Thanks for update and clarification

Post a Comment