[Paraphrased transcript from the eponymous BBC Four programme on British science fiction.]

One theme that has dominated British science fiction is evolution: where have we come from? Where are we going? What will we change into? What will we become?

“I drew a breath, set my teeth, gripped the starting lever, and went off with a thud. The night came like the turning of a lamp, and in another moment came tomorrow. Tomorrow night came black, then day again. Night again, day again, faster and faster still. As I put on pace, night followed day like the flapping of a black wind.” (The Time Machine, 1895, H. G. Wells)

In 1895, in London, H. G. Wells invented time-travel, and science-fiction along with it. Alien invasions, bizarre aliens, trips to the moon – in the following five years, he wrote the novels that would define the folklore of the technological age. There was no such thing as science fiction (or scientific romance, as he called it) before him, or at least none that could be really classed as a genre, but by the time Wells, a man of prodigious imagination was done with it, it was firmly established in the popular mind. This dazzling creative flurry owed much to the permeation of science into public consciousness, something that had fascinated Wells since he was a fifteen-year-old boy.

Wells studied biology at Imperial College, London, then became a journalist, scraping a living writing about science. The Time Machine was his first novel, and, perhaps, his most important. At the time there was much discussion about the fourth dimension, about time as that fourth dimension distinct from the three dimensions of space, but which enabled it to be something one could move along. Wells took this idea and imagined a machine that could move back and forth along this time axis; this became a clever literary device.

Wells studied biology at Imperial College, London, then became a journalist, scraping a living writing about science. The Time Machine was his first novel, and, perhaps, his most important. At the time there was much discussion about the fourth dimension, about time as that fourth dimension distinct from the three dimensions of space, but which enabled it to be something one could move along. Wells took this idea and imagined a machine that could move back and forth along this time axis; this became a clever literary device.

Wells lived in the Machine Age, and his book is clearly Victoriana – all brass and steam and motion. He saw himself as a modern man, part of the vanguard of the ‘new democracy’ that would comprise engineers and scientists that would replace the then ruling class which had been brought up with a classical education and had no idea how to, say, assemble a radio. But for all his fanciful creations, he never forgot that this was not rocket science – instead, it was rocket science fiction. He understood that there probably never would be anti-gravity paint, but that didn’t stop him from using the notion; he recognised that for most readers, the accuracy of the science was less important than whether it sounded accurate.

What was extraordinary about Wells’ time-machine was not how it travelled through time, but how far it went. In mid-Victorian England, there was time but not much of it. Everyone knew when the world had begun – 4070 BC – when God made the earth. But then came Charles Darwin, and history got a lot lot longer. Before him, people had come up with the age of the world by adding up the ages of the prophets in the Bible; Darwin himself had pencilled in various dates in his own copy of the book. His theory, though, pulled the rug from under the Victorians. The Earth was billions of years old. God was nowhere to be seen. But what about the meaning of life? Was man just an ape in sensible shoes?

For the Briton, the static world of religion was a comfort – things had been thus, unchanging, throughout the centuries, and would continue to be the same for the following millennia. But he lived in a period of upheaval, not merely social and economic, but also scientific and technological. The Victorian worldview then became founded on the notion of progress, with the British Empire going ever on, bigger and more powerful, to an even better future. Now, terrifyingly, evolution made progress uncertain; change was the only thing on the menu. And change could be for the worse.

Wells came up then and thought: well, look at the dinosaurs. At the top of the hierarchy they reigned, and at the very pinnacle they died out and became extinct. Was not power and supremacy a mere illusion? Politicians and philosophers were by now co-opting the principles of evolution for their own purposes, to support their own agendas of progress, or (more often) their notions of decay. Entering this debate of progress versus decay, Wells sent his time traveller 800,000 years into the future to see how things had turned up.

What starts as an idyllic view of beauty and peace is quickly shattered; the Victorian view of eternal progress is shattered here. The human race has evolved into two species: the peaceful Eloi who live on the surface, and the brutish Morlock, who lurk underground. Wells’ Darwinian ideas are undercut by the effete, childlike Eloi who are supposed to represent the heightened sensibility and progress of the 1890s Victorians, and the simian, vicious Morlock, so clearly reverted creatures, devolved rather than evolved.

Wells' vision of the future had much to do with his own lowly past. His mother had been a servant to a manorial family; the servants’ quarters were connected to the mansion via subterranean paths, and the servants moved about in that subterranean world. These tunnels must have made an impression on Wells, for the Morlocks – dwellers in the dark spaces - are the ultimate result of the separation of the underdog working class. As an adult, Wells moved among the Eloi elite, but he was never allowed to forget his Morlock past. Aldous Huxley called him a horrid little man; E. M. Forster said he was someone with no taste; all codewords for someone who is not quite ‘one of us’.

To his horror, the Time Traveller, wandering into the caves beneath the Eloi city, discovers just whose blood it is spattered on the walls. The horrendous Morlocks are the top of the food chain in this distant Earth. The aristocratic Eloi are their cattle. If humans can climb up the evolutionary ladder, Wells suggests, humans can equally well fall down it, regress into bestiality. But in the Time Machine, Wells goes beyond the awful class system of the Victorian age – he goes right up to the end of life on Earth. Travelling 30 million years into the future, he finds that (as the common belief went) the Sun is much cooler, like a coal fire that is slowly going out, and since no more fuel is being added, it will soon go out. The world is cold and there’s not much left on it except some giant crabs. It is an extraordinarily bleak vision of a future where neither humanity nor human culture has any relevance. There is no redemption for mankind, no saving of its soul. Wells talks of the oncoming sunset, the oncoming cold, and the oncoming silence.

Evolution, said Wells, does not mean progress. Evolution is change.

The Time Machine set the formula that much of British science fiction was to follow. A lone traveller or scientist. Far-fetched technology only vaguely explained. Strangely evolved creatures, a chaotic universe, a bleak ending. The traveller is not out to conquer but merely to observe, a dilettantish, donnish amateur. And the Time Lords of Doctor Who are the direct descendants of Wells’ own time traveller, an Edwardian gentleman at large in time and space. The only literary image of the time traveller was that of Wells, and that’s why the Time Lords wore Edwardian costume, so unlike the smart uniforms of Star Trek.

Wells’ tale caught the popular imagination, and the critics admired its bold take on Darwin’s ideas. Wells was hailed by the literary elite. Henry James wrote to him, asking if they could collaborate on a work; Joseph Conrad called him the great realist of the fantastic. He was hugely admired by the priests of high culture, which he enjoyed quite as much as the money his success brought him. He kept writing his scientific romances, like the Island of Doctor Moreau, and The Invisible Man. And then he returned once more to contemplate the cruel nature of the evolutionary process, and create the other great staple of science fiction – the alien invader.

As in The Time Machine, with its homey settings and its bicyclesque machine, Wells drew directly on his own time for inspiration. In 1897, London celebrated Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, an occasion celebrated with gusto. But Wells saw the other side of the coin of this imperial pomp. The story goes that he and his brother were discussing the fate of the natives of Tasmania, who had been exterminated by the overpowering strength of the European colonists. Wells looked at the sky and wondered what if the same were to happen to us, the human race, if someone were to land here to colonise us and exterminate us in the same sort of way. The idea was that in the heart of the mightiest empire the world had ever known, a vastly superior force could land and lay waste to it all.

Thinking in evolutionary terms, it is impossible to ever be on top – there would always be someone else more advanced than us, higher beings that could treat the British the way the British treated the Tasmanians. In The War of the Worlds, aliens from a dying Mars invade our planet. They come because they have run out food at home. The people of England become their first course. (Contemplating the destruction of one’s own society has its own satisfaction, and the glee with which Wells lays waste to the Home Counties and London is evident.) Wells showed little sympathy for the annihilated masses. After all, Darwin’s theory implied that the weakest would perish first. His real interest lies in the superior Martians. In his book, he gives us literature’s first alien aliens. And boy, are they ugly.

Thinking in evolutionary terms, it is impossible to ever be on top – there would always be someone else more advanced than us, higher beings that could treat the British the way the British treated the Tasmanians. In The War of the Worlds, aliens from a dying Mars invade our planet. They come because they have run out food at home. The people of England become their first course. (Contemplating the destruction of one’s own society has its own satisfaction, and the glee with which Wells lays waste to the Home Counties and London is evident.) Wells showed little sympathy for the annihilated masses. After all, Darwin’s theory implied that the weakest would perish first. His real interest lies in the superior Martians. In his book, he gives us literature’s first alien aliens. And boy, are they ugly.

Wells found inspiration for his aliens in the specimen jars on the laboratory shelves. He had the idea that as evolution progresses, limbs that are not used will atrophy, shrink and eventually disappear, whereas organs that are used are likely to become larger. The Martians, in short, are us, generations into the future, a caricature of what the man of the future will look like, a standard trope throughout science fiction ever since. Big brains, shrivelled limbs…

In 2005, fans of Doctor Who saw the last Dalek who decides to kill himself because he is contaminated by contact with a human. Shades of Wells’ Martians were obvious – a master race felled by puny foe. The narrator of The War of the Worlds had walked into a deserted, shattered London, and all he could hear was the keening of the last Martian as it lay dying atop Primrose Hill. It seemed that the final tragedy of the novel was not what had happened to the humans, but the extinction of the Martians.

These mighty creatures had been felled by bacteria that humans had developed a resistance to; this denouement was, clearly, very legitimate, as shown in stark relief by the fates of so many white men, Martians of their times, who had gone to Africa, and died there, brought low by diseases that the Africans could tolerate. Wells didn’t know what those diseases were – malaria and other infectious hazards – but he recognised that white people had not evolved resistance to them as the natives had.

Wells had developed yet another template for science fiction. In The First Men on the Moon, a party of dilettante Englishmen travels to our satellite, and find it dominated by a race of giant upright ants with bulging eyes and jointed limbs, the Selenites. This book, with much of its plot changed, was made into a movie in 1964. The writers of the film, however, kept the insectoid aliens. Wells had done what everybody since him repeated – find earthly creatures we are creeped out by, and then make them bigger.

Wells had developed yet another template for science fiction. In The First Men on the Moon, a party of dilettante Englishmen travels to our satellite, and find it dominated by a race of giant upright ants with bulging eyes and jointed limbs, the Selenites. This book, with much of its plot changed, was made into a movie in 1964. The writers of the film, however, kept the insectoid aliens. Wells had done what everybody since him repeated – find earthly creatures we are creeped out by, and then make them bigger.

This was the last book Wells wrote about extraterrestrial life. But many writers took up the gauntlet and boldly went where no Brit had one before. If Wells was the godfather of British science fiction, then Olaf Stapledon would be its prodigal son.

“Seeing the Earth below me was like a huge circular table-top, a broad disk of darkness surrounded by stars. I experienced an increasing exhilaration, and a delightful effervescence of thought. The extraordinary brilliance of the stars excited me. The heavens blazed. The major stars were like the headlights of a distant car. The Milky Way, no longer watered down with darkness was an encircling, granular river of light.” (Star Maker, 1937, Olaf Stapledon)

Stapledon was the great British science fiction writer of the interwar period. Little-known now, he inspired the writers that were to follow. He was the son of a Liverpool shipping magnate, and had experienced war first-hand as an ambulance driver. He told his future wife, “I am sick of dealing with shattered human beings. Each single little tragedy is a mere atom of the whole.” After the war, he became a teacher at a working man’s college; by night, he taught philosophy; by day, he drew up plans for the future history of mankind. His daughter remembers growing up in a house where a portion of the roof had been cut away to make space for a giant telescope.

In his first novel, Last and First Men, Stapledon worked out a detailed projection of human evolution in the cosmos. He describes the rise and fall of eight human species, one after the other, beginning with us, the first men. But in his book Star Maker, Stapledon went even further and took his readers beyond the infinite. It is a mental voyage, a projection by a man atop a hill, into the farthest reaches of space, in search of the great overall ruling force, the Star Maker. He describes world after world, each with its own distinctive cultures and philosophies, and as he goes farther out, encompasses not just this universe, but attempts to show it as an element in a string of many many universes. And it is not just the trajectory of our evolution that attracts his attention, but also other trajectories, alternative speciations and developments of life, and their own journeys through life. Stapledon tests evolutionary theory in his imagination, because, as is evident, it is difficult to ascertain its limits when there is only one test case available – namely, our own. And he places our own evolution in a much broader context, taking Wells’ future of mankind into a mystical meeting with the Star Maker himself.

In his first novel, Last and First Men, Stapledon worked out a detailed projection of human evolution in the cosmos. He describes the rise and fall of eight human species, one after the other, beginning with us, the first men. But in his book Star Maker, Stapledon went even further and took his readers beyond the infinite. It is a mental voyage, a projection by a man atop a hill, into the farthest reaches of space, in search of the great overall ruling force, the Star Maker. He describes world after world, each with its own distinctive cultures and philosophies, and as he goes farther out, encompasses not just this universe, but attempts to show it as an element in a string of many many universes. And it is not just the trajectory of our evolution that attracts his attention, but also other trajectories, alternative speciations and developments of life, and their own journeys through life. Stapledon tests evolutionary theory in his imagination, because, as is evident, it is difficult to ascertain its limits when there is only one test case available – namely, our own. And he places our own evolution in a much broader context, taking Wells’ future of mankind into a mystical meeting with the Star Maker himself.

Up until the 1930s, British science fiction had existed in a cocoon of its own. In the 1940s, Britain experienced an alien invasion of another kind – over-coloured, overblown and over here: American sci-fi pulp appeared on these shores. They were to be found in Woolworths’ department stores, in a magazine section called the Yank Mags, which were sold off very cheap, having arrived on transatlantic liners from New York, having been used as ballast. They took science fiction to a popular audience that had not looked into the genre since the time of Wells. Exciting, vivid and easy to read, they promised a more optimistic future than British readers were used to. This time progress was all set to triumph.

The protagonist in an American popular novel is one who owns the action, who achieves the world that we all deserve. He conquers new frontiers, very much a spin-off of the ever-popular Western genre; the American science fiction is all about space being the new frontier, and develops a programme of advancement from the colonisation of the moon to the galactic empire. This outgoing style of American sci-fi had a big impact on British readers. In the post-war years, it was an optimism people were eager to embrace. In British films such as Fire-Maidens from Outer Space, moviegoers took the stars with pioneering zest. Schoolboys under cover of study devoured the adventures of Dan Dare, Britain’s Flash Gordon. Families gathered to listen to the BBC’s own Journeys into Space.

The protagonist in an American popular novel is one who owns the action, who achieves the world that we all deserve. He conquers new frontiers, very much a spin-off of the ever-popular Western genre; the American science fiction is all about space being the new frontier, and develops a programme of advancement from the colonisation of the moon to the galactic empire. This outgoing style of American sci-fi had a big impact on British readers. In the post-war years, it was an optimism people were eager to embrace. In British films such as Fire-Maidens from Outer Space, moviegoers took the stars with pioneering zest. Schoolboys under cover of study devoured the adventures of Dan Dare, Britain’s Flash Gordon. Families gathered to listen to the BBC’s own Journeys into Space.

Britain even tried to go to space for real. Project Y was a top-secret British-Canadian venture to develop a flying saucer; the British rocketry programme Blue Streak also aimed high. In the years leading up to the moon-landing, Britain was suffused with a spirit of scientific possibilities; there was much appetite for technology and optimism for futuristic developments. Freeze-dried food and washing machines that looked like spaceships were only a glimpse into that future.

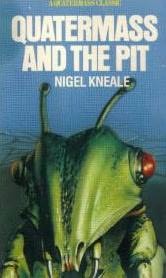

But of course one can only have so much freeze-dried food, and in the 1960s, British science fiction began to return to the exploration of the darker consequences of evolution. The three Quatermass series written by Nigel Kneale were a successful combination of American chutzpah and British sensibility. These were some of the first great sci-fi developments that emerged out of television. And although the sets were cardboard and the plots were more of the gosh! wow! space ranger stuff, cleverly, the series were promoted as thrillers, and that meant that the mainstream audience, which would have avoided them thinking they were Buck Rogers for kids, began to watch them avidly.

In the third (and most sophisticated) of the series, Quatermass and the Pit, the professor discovers the wreckage of an old spaceship, and the bodies of long-dead Martians. Having destroyed their own planet, the Martians had fled to Earth many millennia ago. The professor eventually discovers that it was the Martians who had planted the seeds of life that led to human evolution on Earth. To wit, we are their descendants. And this was a shock, because the Martians were nasty, always fighting wars and killing each other – and then, realisation dawns: aren’t we doing the same thing? “We are the Martians. And if we cannot control their inheritance within us, this will be the second dead planet.”

In the third (and most sophisticated) of the series, Quatermass and the Pit, the professor discovers the wreckage of an old spaceship, and the bodies of long-dead Martians. Having destroyed their own planet, the Martians had fled to Earth many millennia ago. The professor eventually discovers that it was the Martians who had planted the seeds of life that led to human evolution on Earth. To wit, we are their descendants. And this was a shock, because the Martians were nasty, always fighting wars and killing each other – and then, realisation dawns: aren’t we doing the same thing? “We are the Martians. And if we cannot control their inheritance within us, this will be the second dead planet.”

Nigel Kneale’s story was a neat Cold War twist on H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. For another 1950s writer, the relationship between us and the aliens was about to become a lot more intimate. For John Wyndham, it wasn’t bug-eyed monsters we should be frightened of, but our own children. The Midwich Cuckoos was written in 1957 and was one of the best-selling books of the decade. It played straight into the anxieties of the time. It seemed to reflect what would soon be known as the generation gap, and mirrored the feelings of many parents that their children were much more intelligent than they were, particularly among the working class and the lower-middle-class folks of the 1950s, whose kids went to grammar schools and came home, and appeared to have become aliens overnight. The Midwich Cuckoos soon outstrip the adults around them by light-years, and begin to threaten their survival. It is an old-style evolutionary battle between normal humanity, and the new, improved model – Homo Superior. The adults decide the kids must go, and blow them all up.

The Midwich Cuckoos was a rarity in British science fiction, in that it was turned into a movie. Renamed The Village of the Damned, it was a smash hit in 1960. It showed that one of the things that distinguished British sci-fi from American sci-fi was that the British liked things small, intimate; there was no need for expensive sets of futuristic civilisations, and silver togas and fancy spacecrafts; find a small village near Shepperton that looks like Midwich, and voila! America enjoyed the idea of eight thousand spaceships arriving on a planet and laying it waste; the British thought that six well-spoken children were equally scary.

The Midwich Cuckoos was a rarity in British science fiction, in that it was turned into a movie. Renamed The Village of the Damned, it was a smash hit in 1960. It showed that one of the things that distinguished British sci-fi from American sci-fi was that the British liked things small, intimate; there was no need for expensive sets of futuristic civilisations, and silver togas and fancy spacecrafts; find a small village near Shepperton that looks like Midwich, and voila! America enjoyed the idea of eight thousand spaceships arriving on a planet and laying it waste; the British thought that six well-spoken children were equally scary.

In both film and book, the children were the result of overnight insemination of humans by aliens. A one-night stand of the third kind, so to speak. Another 1950s writer, Arthur C. Clarke, had an even bolder vision of the role of aliens in evolution. His book, Childhood’s End, begins with a scene that has been copied again and again in films, most recently in Independence Day. Both novel and film, the action begins with giant spacecraft arriving and hovering above the cities of the Earth. It is culture shock on a vast scale, akin surely to that experienced by natives witnessing the arrival of Captain Cook’s flotilla.

.jpg) Clarke was a technocrat, a man who had made real contributions to telecommunications and the development of satellite technology. His attitude to aliens was far more optimistic than either Wells’ or Wyndham’s – one could sense that he really wanted to meet them himself. His aliens have come neither to conquer us nor eat us. Their purpose is to trigger mankind into an evolutionary leap, to become a species with superior powers. In Clarke’s novel, a single generation of children makes a startling jump – they achieve telepathy and are able to link their minds. At the end of the book, the last old-style humans watch as their younger, super-offspring ascend to join the Overmind in the stars.

Clarke was a technocrat, a man who had made real contributions to telecommunications and the development of satellite technology. His attitude to aliens was far more optimistic than either Wells’ or Wyndham’s – one could sense that he really wanted to meet them himself. His aliens have come neither to conquer us nor eat us. Their purpose is to trigger mankind into an evolutionary leap, to become a species with superior powers. In Clarke’s novel, a single generation of children makes a startling jump – they achieve telepathy and are able to link their minds. At the end of the book, the last old-style humans watch as their younger, super-offspring ascend to join the Overmind in the stars.

What Clarke achieves is to reintroduce the notion of intent behind evolution, that is, a benign force that is ever guiding our progress to greater ability and achievement. This is, really, another version of intelligent design, that, at critical moments, intervenes and nudges us towards perfection. Fundamentally, then, it is a very religious idea, except that, unlike other religions that tout the supremacy of humanity, here we achieve a union with millions of other elevated species, becoming thereby one among many that have attained perfection.

By the early 1960s, real life was pressing close on science fiction’s heels. In 1961, President Kennedy unveiled a grand plan to set a man on the moon by the end of the decade. As America’s space programme developed, space fever intensified much more in Britain, perhaps because the British didn’t have to pay for it. Every child in the playground wanted to be an astronaut. It was a commonplace then that by the year 2000, we’d all be able to go to the moon with the same ease that we now take trips to the beach in Spain. Then, in 1968, came a film that united space obsessed kids and space obsessed adults alike. 2001: A Space Odyssey, co-written by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, and directed by Kubrick intended nothing less than to be the greatest science fiction movie ever (Clarke thinks it succeeded), and describe the progress of humans from their origins through to the very distant future. In many ways, it was much more ambitious than Childhood’s End, but it still had the underlying theme of an external force that guides our evolution. Clarke is an optimist, clearly, although he is cynical enough to realise that mankind would protest and baulk at such external guidance of its fate. Kubrick wasn’t entirely sure that the aliens were quite as benevolent as Clarke thought they were, which makes 2001: A Space Odyssey an ambiguous work, and thus superior to Childhood’s End.

By the early 1960s, real life was pressing close on science fiction’s heels. In 1961, President Kennedy unveiled a grand plan to set a man on the moon by the end of the decade. As America’s space programme developed, space fever intensified much more in Britain, perhaps because the British didn’t have to pay for it. Every child in the playground wanted to be an astronaut. It was a commonplace then that by the year 2000, we’d all be able to go to the moon with the same ease that we now take trips to the beach in Spain. Then, in 1968, came a film that united space obsessed kids and space obsessed adults alike. 2001: A Space Odyssey, co-written by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, and directed by Kubrick intended nothing less than to be the greatest science fiction movie ever (Clarke thinks it succeeded), and describe the progress of humans from their origins through to the very distant future. In many ways, it was much more ambitious than Childhood’s End, but it still had the underlying theme of an external force that guides our evolution. Clarke is an optimist, clearly, although he is cynical enough to realise that mankind would protest and baulk at such external guidance of its fate. Kubrick wasn’t entirely sure that the aliens were quite as benevolent as Clarke thought they were, which makes 2001: A Space Odyssey an ambiguous work, and thus superior to Childhood’s End.

At the end of the film, a lone astronaut is projected into the far reaches of space, rather like Stapledon’s anonymous Star Maker hero of thirty years before. He travels to Jupiter and beyond, and is reborn into the next stage of evolution. The way this is portrayed is by an embryo, as though to determine a new beginning we have to go back to our own beginnings. Clarke’s work is a spiritual quest. Although he grew up in a religious family, he himself was anti-religious, but his books deal with much of the yearning and desire to learn of God’s purpose for us.

Since its beginnings, British science fiction has been dealing with the effect of evolution on the meaning of life. Wells created a Godless universe with decay as likely as progress. Stapledon conjured up a sort of blind watchmaker, tinkering with evolution without any sense of purpose. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Clarke and Kubrick reinvented an old-fashioned spirit-in-the-sky. For centuries people had been imagining what it would be like to leave the gravitational pull of the Earth. At the tail-end of 1968, it happened, the moment when reality caught up with science fiction. Millions watched as the astronauts of Apollo 8 became the first men to leave the Earth’s orbit. As Clarke famously said at the time, we were now living in the future.

3 comments:

that was one hell of an article. lots of research there.

keep up the good work

static variable: thanks for stopping by, and the kind words. feel free to browse the rest of the blog!

Superbly done...Posted on another site (copyright? Forgive me, I have no money, don't sue me:)...Received nothing but the highest praise as a post well done)...It is "one hell of an article" (Thank you oh mighty scriptwrighter 'Static variable'...

A little intelligence does not go astray in the either after all?...

Keep up the good work. It is very much appreciated in the grey, grey world that is ours...

Cheers and all the very...David, with love.

Post a Comment