Recently, my favourite art historian and all-round bonhomous man Andrew Graham-Dixon has been appearing recently on quite a few television series. I saw him on Oliver Peyton's Eating Art (mentioned here). Besides this, he presented an interesting bio of Johnny Rotten, the lead of the Sex Pistols, and two series on art: Early Christian and Russian. I was reminded of Graham-Dixon's glee on encountering some of the avant-garde art of the early Soviet period when I came across Mark Grigorian's post on an exhibition of the Turkestan Avant-Garde at the State Museum of Oriental Art in Moscow. In other words, I was equally gleeful.

The exhibition will end on April 15 this year, and if you are in Moscow, it should be high on your list of things to see. Unfortunately, I won’t be there and shall not see it.

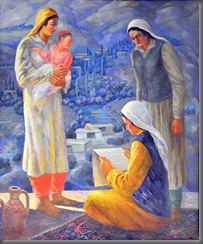

As Mark points out, a remarkable event occurred in early 20th century Russia. Artists trained in the avant-garde in Moscow go to the Ferghana Valley and develop for themselves a new style that blends a Russian sensibility with the exotic and unusual Turkic one.

There’s not only paintings at the exhibitions – there are cartoons and etching and even ceramic work. Much of it is inspired by Soviet ideology (‘Tractor’ or ‘Physical Education’), but melding nicely with, among other things, Christian symbolism.

There’s not only paintings at the exhibitions – there are cartoons and etching and even ceramic work. Much of it is inspired by Soviet ideology (‘Tractor’ or ‘Physical Education’), but melding nicely with, among other things, Christian symbolism.

The exhibition draws on contributions, among others, from the Russian State Archive of Cinema and Photography (in Krasnogorsk). More than 150 exponents of the Turkic avant-garde illustrate an exceptional artistic phenomenon of the 20th century. In the main part of the exhibition are works by the masters of the movement, people such as Alexander Volkov, N. Karahan, Ufimtsev, Karavai, Kashin, Tateossian, Shegolev, Gaidukevich, Kurzin, Eremyan, and others. Painters from all corners of Russia had descended upon Turkestan in search of vivid impressions and a new descriptive form. They blazed a new path in Central Asia, building upon the traditional easel-based arts and local culture. The unfamiliar lifestyles and customs served as fertile ground for creative experimentation for these artists of the European school.

The exhibition draws on contributions, among others, from the Russian State Archive of Cinema and Photography (in Krasnogorsk). More than 150 exponents of the Turkic avant-garde illustrate an exceptional artistic phenomenon of the 20th century. In the main part of the exhibition are works by the masters of the movement, people such as Alexander Volkov, N. Karahan, Ufimtsev, Karavai, Kashin, Tateossian, Shegolev, Gaidukevich, Kurzin, Eremyan, and others. Painters from all corners of Russia had descended upon Turkestan in search of vivid impressions and a new descriptive form. They blazed a new path in Central Asia, building upon the traditional easel-based arts and local culture. The unfamiliar lifestyles and customs served as fertile ground for creative experimentation for these artists of the European school.

They didn’t just selfishly absorb the Oriental exoticism; they also contributed to the region, restoring architectural monuments and establishing art schools. They became the teachers that trained the first generation of national painters and sculptors and graphic artists in Central Asia.

They didn’t just selfishly absorb the Oriental exoticism; they also contributed to the region, restoring architectural monuments and establishing art schools. They became the teachers that trained the first generation of national painters and sculptors and graphic artists in Central Asia.

By the time the avant-garde began to decay in Russia, hitherto recognised as a leader of the genre, in Central Asia there continued a thriving culture of bright innovation, original products impregnated by local colour, filled with fresh compositional decisions, and untainted by Socialist realism.

By the time the avant-garde began to decay in Russia, hitherto recognised as a leader of the genre, in Central Asia there continued a thriving culture of bright innovation, original products impregnated by local colour, filled with fresh compositional decisions, and untainted by Socialist realism.

(The last three pictures are from the State Museum of Oriental Art.)

0 comments:

Post a Comment