There's an entire world of poetry, literature and art devoted to the railways. Imagine three London stations, and imagine the references that suffuse them: Sherlock Holmes at St Pancras, or Harry Potter at King's Cross, or Dombey at Euston. What is the source of the railways' mystique? And why have they inspired litterateurs from William Wordsworth to J. K. Rowling?

Locomotives and the atmosphere they brew have been a source of inspiration for writers and poets for the past two hundred years. In Edwardian times, the railways were the lifeblood of the nation, the starting point of all adventures. A big station like York was a microcosm of the society it served. Here a writer like Andrew Martin could bring together characters like travelling gentlemen and chimney sweeps on the move. Station guards contended with cutpurses and station loungers and other species of railway riffraff. Stations teemed with life.

Martin set his novels in the Edwardian period because that was the zenith of the British rail network. His father had worked in the finance department of British Rail at York, and forever having to come up with cut backs. His novels were his vicarious revenge.

His father was railway aristocracy; not only was he able to travel at will in first class, but so was his family. Martin would occasionally take the train to London as a fourteen-year old boy, lounging comfortably in a first class seat, reading a book. A harassed-looking businessman would huff up to him and say, 'Are you aware you are in a first-class seat, young man?' to which he would reply, 'Yes, I am, thanks.' and return to his book.

Trains, he said (and I heartily agree), are superior to cars. You can read on trains. You will only feel sick in a car. Trains have a wgealth of culture behind them. Cars have not.

Train travel was not always so sedate. A hundred and fifty years earlier, you might have been gripping the armrests of your seat in quiet panic rather than read a book. Imagine your shock of a speeding train when the fastest thing you had ever seen before was a stagecoach. You thought your brains would fly out of your ears at that speed.

|

| Turner's Rain,Steam and Speed [Wikimedia Commons] |

One day in 1843 the artist Turner was travelling on the Great Western Railway. He stuck his head out of the window of a first class carriage during a rainstorm. He was most forcibly impressed. He was met with the demonic force of speed through a cloud of smoke and rain. The experience gave birth to his painting 'Rain, Steam and Speed - the Great Western Railway'. If you want to be pedantic about it, you would say that the painting shows a Gooch Firefly 222 locomotive. That's hardly the point. The image to the viewer is that of a bullet aimed straight at the heart.

Andrew Martin got into trouble at the National Gallery when he leaned too close to the painting when showing his son the hare running ahead of the locomotive. The hare, a very fast animal, is being caught up by the engine. Man is getting the upper hand over nature.

The advent of the railway in Britain was cataclysmic, concentrated into a few frenetic years. Nine-tenths of the current mileage were authorised in three years from 1844. These vast iron gatecrashers thundered through back gardens, cellars, beautiful meadows and social conventions. From the outset, they attracted the scornful eye of writers and anyone with a vested interest in contemplation. In 'a just disdain', Wordsworth wrote of England being blighted by steam.

Now, for your shame, a Power, the Thirst of Gold,

That rules o'er Britain like a baneful star,

Wills that your peace, your beauty, shall be sold,

And clear way made for her triumphal car

A lightning rod for the railways anxieties of the time was Charles Dickens. His railway novel Dombey and Son contains one of the first descriptions of the landscape flickering past the train window.

Through the hollow, on the height, by the heath, by the orchard, by the park, by the garden, over the canal, across the river, where the sheep are feeding, where the mill is going, where the barge is floating, where the dead are lying, where the factory is smoking, where the stream is running, where the village clusters, where the great cathedral rises, where the bleak moor lies, and the wild breeze smooths or ruffles it at its inconstant will; away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, and no trace to leave behind but dust and vapour: like as in the track of the remorseless monster, Death!

A theme of Dombey and Son is the destruction wrought by the building of the London to Birmingham line that runs to Euston station. This was the first railway to come into North London. Unfortunately when it came to be built in the 1830s, Camden happened to be in the way. Dickens was a man attached to the idea of Merrie England, and much attached to the stagecoach. In his book, he referred to Camden as Staggs' Gardens. He knew the area well, having been brought up here when it had been more or less a village. During the construction of the railway he saw places he knew, including part of his old school, being destroyed. He was morbidly fascinated by the process.

The railways were omnipotent, and so like many other works of the time, Dombey and Son features a death by locomotive. The treacherous Carker is run over by a train; he

felt the earth tremble—knew in a moment that the rush was come—uttered a shriek—looked round—saw the red eyes, bleared and dim, in the daylight, close upon him—was beaten down, caught up, and whirled away upon a jagged mill, that spun him round and round, and struck him limb from limb, and licked his stream of life up with its fiery heat, and cast his mutilated fragments in the air.

It wasn't just the gutting of towns and villages that seemed wrong to the sensitive literary folk. The locomotives themselves appeared to be demonic powers, with a killing edge to them. In Anthony Trollope's The Prime Minister, the villain Lopez is 'knocked to bloody atoms' by a shrieking Scottish express. In Leo Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, the heroine commits suicide by leaping in front of an oncoming engine. Locomotives didn't just appear to be murderous figments of the imagination - they did have an unfortunate habit of killing people. Steam engines, scary enough when stationary, were whirled about the country at fantastical speeds. At the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830, a Cabinet Minister, William Huskisson, was knocked down and killed. No wonder the government has been so reluctant to fund the railways ever since.

It was a simple equation: more railways meant more deaths. The 1860s were the darkest period when gory stories of mayhem caused by trains were rarely off the headlines. These 'smashes', as they were known, magnetised and repelled the Victorians in equal measure. Here was a very modern way to die.

In the 1860s, there were more trains on the same lines, going ever faster, the chances of collision ever so greater. The authorities did little to enforce safety standards till the 1880s.

Cartoonists portrayed the locomotives as beasts, dragon-like, intent on the destruction of mere humans. Returning from France on 9 June 1865, all of Charles Dickens' fears of the railways came true, when he was involved in a terrific crash near Staplehurst in Kent. The accident was caused by a work-gang lifting tracks off a viaduct. They had reckoned without the 2.38 from Folkestone to London.

Dickens helped soothe the injured and the dying with a flask of brandy and cool water in his top hat. Ten people died in the crash, and for the rest of his life, all of Dickens' anxieties would be subsumed by the greater one over Staplehurst.

The accident prompted him to write one of his greatest ghost stories, 'The Signal-Man'. A superbly gloomy version appeared on TV every Christmas during Andrew Martin's childhood. The story concerns a signal-man stuck in a cutting next to a glowering red light. He is at the mercy of an electric bell and the necessity of showing his red flag as a train rolled past. He is a fascinatingly neurotic man with many interests. He has taught himself a language whilst in his signal box, he has worked at decimals and fractions. But he is tormented by the loneliness of his job, the memory of two previous accidents, and a premonition of a third. He constantly feels the urge to send the telegraphic signal 'Danger. Take care.' but he can't say why. Of course, a smash is looming.

Dickens has often been described as the last victim of the Staplehurst accident. Later in life he attributed his ill health to 'railway shaking'. He died on the fifth anniversary of the crash.

In the 19th century, the railways shaped culture in other, benign, ways. People began to read on trains, and so in 1848, W.H. Smith opened their first railway bookstore at Euston Station. Books sold in stations were the forerunners of the airport novel: a new genre, inexpensive, with plots that could hold a passenger's attention throughout the distractions of a train journey, all that stopping and starting and 'Excuse me, is this the train for Birmingham?' As Cecily said in Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest : "One should always have something sensational to read in the train."

An entire industry of sensationalist literature developed, with writers competing for the riders' attentions, and for shelf-space on W.H.Smith's stores. Between garish covers, there was everything the man or woman on the 2.22 desired: sex, insanity, and above all, violent death.

Cheaply bound thrillers were known as 'yellow backs' and their authors, such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon, sold in their thousands from the railway bookshops. The success of Braddon irritated George Eliot, who wrote to her publisher: 'I suppose the reason my own six shilling editions are never on the railway stalls is that they are not so attractive to the majority.' One reviewer of Braddon's work expressed regret that a book 'without a murder, a divorce, a seduction, or a bigamy, is not apparently considered either worth writing or reading.'

The Victorian sensation stories would play upon their readers' anxieties about railway travel. A woman sitting alone in a carriage might read about a woman sitting alone in a carriage, except that in the story, a strange man would leap in through the window, a strange man with a top hat and a moustache. Such breaches of compartment etiquette would be depicted later in the cinema, as in Alfred Hitchcock's version of John Buchan's The Thirty-Nine Steps where Robert Donat's character bursts in on Madeline Carroll, while she is reading, alone.

Hitchcock was no trainspotter, and his film contains one notorious mistake (notorious among the persnickety sticklers, that is). When Hannay leaves for Scotland, he is on the London and Northeastern train, as he should be. Hitchcock cuts away here, and when he cuts back, the train that is next shown is a Great Western emerging from Box Tunnel near Bath.

In the original novel, trains are marginal, but Hitchcock uses them to boost the speed and tension of the narrative. But he also made use of another tension involved in train travel: that of not being entirely sure who your travelling companions are. Walter de la Mare wrote: 'It's a fascinating experience, railway travelling. One is cast into a passing privacy with a fellow stranger, and then it is gone.'

By the end of the 19th century, trains had been tamed and were no longer a danger in themselves. They had become comprehensible. When Sherlock Holmes rode on a train, the journey was not a worry in his mind.

An entire industry of sensationalist literature developed, with writers competing for the riders' attentions, and for shelf-space on W.H.Smith's stores. Between garish covers, there was everything the man or woman on the 2.22 desired: sex, insanity, and above all, violent death.

Cheaply bound thrillers were known as 'yellow backs' and their authors, such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon, sold in their thousands from the railway bookshops. The success of Braddon irritated George Eliot, who wrote to her publisher: 'I suppose the reason my own six shilling editions are never on the railway stalls is that they are not so attractive to the majority.' One reviewer of Braddon's work expressed regret that a book 'without a murder, a divorce, a seduction, or a bigamy, is not apparently considered either worth writing or reading.'

The Victorian sensation stories would play upon their readers' anxieties about railway travel. A woman sitting alone in a carriage might read about a woman sitting alone in a carriage, except that in the story, a strange man would leap in through the window, a strange man with a top hat and a moustache. Such breaches of compartment etiquette would be depicted later in the cinema, as in Alfred Hitchcock's version of John Buchan's The Thirty-Nine Steps where Robert Donat's character bursts in on Madeline Carroll, while she is reading, alone.

Hitchcock was no trainspotter, and his film contains one notorious mistake (notorious among the persnickety sticklers, that is). When Hannay leaves for Scotland, he is on the London and Northeastern train, as he should be. Hitchcock cuts away here, and when he cuts back, the train that is next shown is a Great Western emerging from Box Tunnel near Bath.

In the original novel, trains are marginal, but Hitchcock uses them to boost the speed and tension of the narrative. But he also made use of another tension involved in train travel: that of not being entirely sure who your travelling companions are. Walter de la Mare wrote: 'It's a fascinating experience, railway travelling. One is cast into a passing privacy with a fellow stranger, and then it is gone.'

By the end of the 19th century, trains had been tamed and were no longer a danger in themselves. They had become comprehensible. When Sherlock Holmes rode on a train, the journey was not a worry in his mind.

"We are going well," said he, looking out of the window and glancing at his watch. "Our rate at present is fifty-three and a half miles an hour."

"I have not observed the quarter-mile posts," said I.

"Nor have I. But the telegraph posts upon this line are sixty yards apart, and the calculation is a simple one..."

Holmes and Watson depart from every terminus in London save Marylebone. The only reason for that lacuna is that it was built too late, in 1899, by which time they were almost done. And they were never above recourse to that humble document, the railway timetable.

Until the 1960s, British railway timetables were called Bradshaws, after the man who started publishing them in 1841. They were thick as bricks, and filled with exasperating footnotes such as 'except Mondays' and 'should the arrival of the steamer be late, the train will not stop.' In those days, a man would have a Bradshaw as readily to hand as one would have car keys today. But often Dr Watson didn't need a Bradshaw - he knew the times of the trains without having to look them up. In 'The Retired Colourman', for instance, Holmes asks Watson to look up the train times to Little Pearlington in Essex, and despite the bizarre obscurity of the destination, the latter immediately replies, 'There is one at 5.20 from Liverpool Street.' We have the beginnings of that fantastic sub-genre of literature where the pedantry of detective fiction is combined with the even more pedantic railway timetable, resulting something evermore pedantic: a murder mystery with train timings at its core.

Take Agatha Christie's novel, 4.50 from Paddington. A timetable and a map provide Miss Marple with vital clues to a murder witnessed on a passing train. In the snappily titled film version ('Murder, She Said', 1961, directed by George Pollock), Miss Marple says:

"Ah yes, here we are. Now, I calculate the 5 o'clock express to Brackhampton overtook my train somewhere about here.""But how can you be sure?" "I remember the ticket collector saying 'Five minutes to Brackhampton', and it couldn't have been more than a minute after the murder that he came in. So that makes it six minutes before Brackhampton, at, say, 30 miles an hour. So that makes it about ... there."

The apex (or nadir) of this sub-genre is The Cask, a 1920 novel by Freeman Wills Crofts, which is all about the logistics of transporting by rail a particular barrel, which contains a dead body. Crofts was an engineer, and he wrote like an engineer. His novel seemed as full of numbers as of letters:

He looked at the timetable again. The train in question reached Calais at 3.31 and the boat left at 3.45. That was a delay of 14 minutes. Would there be time, he wondered, to make two long-distance phone calls in fourteen minutes?Obsession with numbers could then easily be satirised, as in this sketch from Monty Python.

|

| Oakworth Station (from here) |

The book came out in 1906, and by then the British were thoroughly used to railways in their every day lives. Trains could be seen as cosy and whimsical, as well as potentially dangerous. Far from being despoilers of the landscape, they had become an integral part of it. They were no longer Gothic, but sentimentalised and loved. For the Railway children, the trains were an idyll and a joy. Nesbit writes: 'The rocks and hills and valleys and trees, the canal, and above all, the railway, were so new and so perfectly pleasing that the remembrance of the old life in the villa grew to seem like a dream.'

|

| John Hassall (printed for the LNER by Waterlow & Sons Ltd London) |

Giving names to trains, such as the Flying Scotsman, only added to the mystique of train travel. The romance of rail lasted well into the 1950s. In that time, the weirdos and the misfits were the boys not interested in trains. Between 1911 and 1950, The Wonderbook of Railways for Boys and Girls went through twenty-one editions. It is filled with detailed accounts of railway workings. A chat with an engine driver, and Mr Brown the signal-man. At the same time, railway stories were being written for children in their thousands: Life or Death, The Indian Rail Yarn, The Missing Mail Bag...

The perfect evocation of the railways in England is often taken to be in the form of a poem, Adlestrop by Edward Thomas. On the face of it, the poem recalls a non-event. Thomas' train makes an unscheduled stop in Adlestrop in Gloucestershire. Nothing happened, but the tranquillity of the moment and the sense of time suspended across the sunny English countryside stayed with Thomas.

Yes, I remember Adlestrop –That kind of poignancy could only have been generated retrospectively. His diary records the date of the stop: June 23, 1914. But the poem was written when he was serving in the British Army in the World War I, in which he would be killed. The view of the railways became firmly imprinted on the nation - through a haze of nostalgia.

The name because one afternoon

Of heat the express-train drew up there

Unwontendly. It was late June.

The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop – only the name

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.

During the Great War, the railways took on another significance - they took soldiers to the front, and brought them in rather fewer numbers back. As the public gained familiarity with terms such as 'ambulance carriage' and 'hospital train', the word 'departure' took on a more ominous meaning. Marcel Proust said railway stations were inherently tragic places because they carried people into the unknown. Imagine how much the stakes were raised for wartime departures. Thomas Hardy's poem 'In A Waiting Room' from a collection published in 1917 captures the leave-taking on a wet morning, described as being 'sick as the day of doom.'

A soldier and wife, with haggard look

Subdued to stone by strong endeavour;

And then I heard

From a casual word

They were parting as they believed for ever.

In the poem, the soldier and his wife are only two characters in a waiting room filled with others. The narrator's attention is quickly diverted by some laughing children. The private agony of the parting couple is swiftly put aside.

In WWII, the collision of personal misery and mundane chatter in the waiting room was brought to the cinema. David Lean's 'Brief Encounter' beautifully realised this. In the film, the railway station is described as 'the most ordinary place in the world', but where an earlier tormented heroine might have flung herself onto the tracks like Anna Karenina, in the 1940s, the worst a locomotive can do is to fling a bit of grit into Celia Johnson's eye.

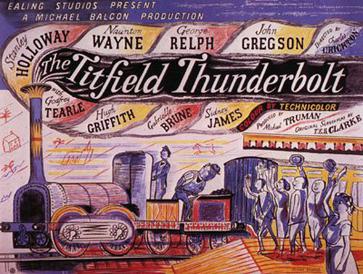

After the war, Britain focused on becoming a modern nation, and the feelings of affection it had held for the train were transferred, for a while at least, onto the motor car. The railways were nationalised, and the romance began to wear off. It was the car that could now take you to picturesque backwaters of the land, and you no longer had to share space with people who picked their teeth in an annoying way, or were just plain murderous-looking. Like a man with a mid-life crisis, trying not to look old-fashioned, people began to look upon trains as second class, a social service for those who were too poor or decrepit to drive. That moment of transition was captured by the 1953 film, 'The Titfield Thunderbolt'. Here a cherished branch line is threatened by a local bus service, and the competition between rail and road is played out for the cameras.

Ironically, in real life, that branch line had already been closed. A BBC crew filmed the making the movie, including the famous scene of the runaway train. The scriptwriter was a neighbour of Dr Beeching, the future chairman of the British Railways Board, and slayer of branch lines.

Given the aesthetic appeal of the railways, it is not surprising that a poet became their greatest champion when they came under attack. 'Rumble under, thunder over, train and tram, alternate go' he wrote:

In WWII, the collision of personal misery and mundane chatter in the waiting room was brought to the cinema. David Lean's 'Brief Encounter' beautifully realised this. In the film, the railway station is described as 'the most ordinary place in the world', but where an earlier tormented heroine might have flung herself onto the tracks like Anna Karenina, in the 1940s, the worst a locomotive can do is to fling a bit of grit into Celia Johnson's eye.

|

| (Titfield Thunderbolt film poster, Wikimedia Commons) |

Ironically, in real life, that branch line had already been closed. A BBC crew filmed the making the movie, including the famous scene of the runaway train. The scriptwriter was a neighbour of Dr Beeching, the future chairman of the British Railways Board, and slayer of branch lines.

Given the aesthetic appeal of the railways, it is not surprising that a poet became their greatest champion when they came under attack. 'Rumble under, thunder over, train and tram, alternate go' he wrote:

Rumbling under blackened girders,

Midland bound for Cricklewood,

Puffed its sulphur to where that Land of

Laundries stood.

Rumble under, thunder over, train and

tram alternate go,

Shake the floor and smudge the ledger,

Charrington, Sells Dale and Co.,

Nuts and nuggets in the window

Such a dynamic thrust from such unpretentious lines.

For Betjeman, the railways' appeal was their permanence, a treasure bequeathed by our forefathers, 'a Victorian's world and the present, in a moment's neighbourhood.' In his poetry, the railway station stands for a world that is fading or has vanished completely. 'Monody on the Death of Aldersgate Street Station' began:

As Dr Beeching's cuts took hold, so did come the end of the reign of steam. Carnforth, where David Lean's Brief Encounters was filmed, became the dumping ground for the disused locomotives.

Diesel had none of the romantic elegance of the old steam. And today, even locomotives appear to be on their way out. Instead, we have multiple units that are as graceful and aerodynamic as wardrobes, with charmless names like 365 class. They are functional, and like worms, they can still move after being chopped in half. But they are hardly going to inspire our writers.

The great stations of times past are distressingly anodyne today. At York, the signal cabin is now a Costa Coffee; the night station master's cabin (a location for a strangely, even satanically, compelling job description) is a tourist information centre; the old booking hall is a Burger King. Stations are no longer about the business of railways. They are in the business of retail. The mysterious soot-blackened hinterlands have been tidied away. We are passengers no longer. We are officially customers, consumers, of course.

The railway satirist who writes under the name Tyresius has updated Adlestrop for the modern day:

For a revival of literary focus on the railways, the high-speed Eurostar may offer the only hope in Britain. Two hundred mile-an-hour trains. Champagne on tap in the buffet. Smartly turned out railway staff. A long undersea tunnel - anything could happen in that. For the future of trains to be assured, they much once again become the vehicles of our dreams.

For Betjeman, the railways' appeal was their permanence, a treasure bequeathed by our forefathers, 'a Victorian's world and the present, in a moment's neighbourhood.' In his poetry, the railway station stands for a world that is fading or has vanished completely. 'Monody on the Death of Aldersgate Street Station' began:

Snow falls in the buffet of Aldersgate station,Betjeman appears to elide churches and railway stations, with both offering a refuge from the modern world. It is apt that he was behind the impetus to save St Pancras from demolition; St Pancras being a Christian saint and a railway station.

Soot hangs in the tunnel in clouds of steam.

City of London! before the next desecration

Let your steepled forest of churches be my theme.

As Dr Beeching's cuts took hold, so did come the end of the reign of steam. Carnforth, where David Lean's Brief Encounters was filmed, became the dumping ground for the disused locomotives.

Diesel had none of the romantic elegance of the old steam. And today, even locomotives appear to be on their way out. Instead, we have multiple units that are as graceful and aerodynamic as wardrobes, with charmless names like 365 class. They are functional, and like worms, they can still move after being chopped in half. But they are hardly going to inspire our writers.

The great stations of times past are distressingly anodyne today. At York, the signal cabin is now a Costa Coffee; the night station master's cabin (a location for a strangely, even satanically, compelling job description) is a tourist information centre; the old booking hall is a Burger King. Stations are no longer about the business of railways. They are in the business of retail. The mysterious soot-blackened hinterlands have been tidied away. We are passengers no longer. We are officially customers, consumers, of course.

The railway satirist who writes under the name Tyresius has updated Adlestrop for the modern day:

Haycocks and meadows sweet, I wouldn't know.The few people who write about the railways today are writing about what doesn't exist today, or even what never existed at all. Note that the Hogwarts Express of Harry Potter fame is not a diesel multiple unit. Its departure platform, the fabled nine-and-three-quarters, is a portal to a fantasy land a world away from modern King's Cross. And in the self-consciously cool series of Bourne films, Matt Damon arrives in London not on a plane, but on the Eurostar. This is highly promising.

I never looked outside the train.

Just canned beer from a plastic cup.

Until the damned thing started again.

For a revival of literary focus on the railways, the high-speed Eurostar may offer the only hope in Britain. Two hundred mile-an-hour trains. Champagne on tap in the buffet. Smartly turned out railway staff. A long undersea tunnel - anything could happen in that. For the future of trains to be assured, they much once again become the vehicles of our dreams.

[This is a (very) paraphrased rendition of Andrew Martin's 'Between the Lines: Railways in Fiction and Film', shown on BBC Four.]

2 comments:

Wow. This is one monster post (and about a subject that's very dear to my heart!)

Like poetry, literature and art, there's a whole sub-genre of country, folk and blues music inspired by trains. Now I'm tempted to post a playlist of videos and songs about trains after reading your post.

If you do succumb to that temptation, do let us know - I'd be interested to see that list.

Post a Comment