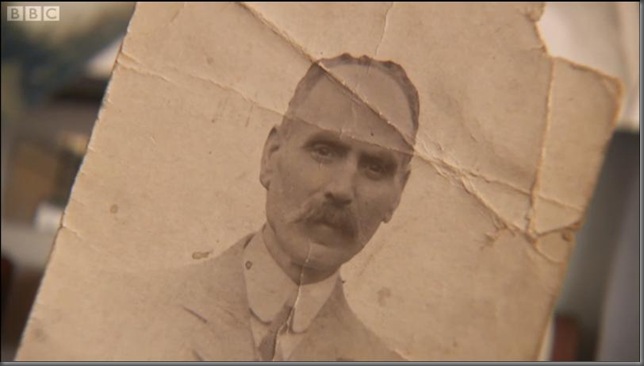

Matthew Gibb (1849-1920), great-grandfather of the Bee Gees, was a military man. According the Scottish records office, he was 5’ 5¾” tall at enlistment at the age of 18 in the 60th Rifles (which later became known as Scottish Rifles, The Cameronians). He was a shoemaker in the parish of Abbey, Paisley, Scotland when he joined up. His eyes were hazel, and his hair was brown. He served in India (1867-1878, 1880-81), Afghanistan (1878-1880), South Africa (1881-1882) and back home in 1882. He was discharged in 1905 with a rank of Quartermaster, after having served nearly four decades with the Forces. His conduct was reported as ‘Exemplary’ and was awarded the Good Conduct medal and the Long Service medal, and another one for combat in Afghanistan.

“In spite of the above mentioned good conduct and decorations, it appears that in 1874 while serving in India, he was arrested for drunkenness, tried, and reduced in rank from Corporal back to Private.”

To his descendants today, this seems entirely out of character, for all his sons were teetotallers, and he himself appears as unbending and stern in his photographs. And yet how could something as trivial as drunkenness result in so harsh a punishment?

The Regimental Headquarters of the 60th Rifles is in Winchester, and the details of Gibb’s service are available in greater detail there.

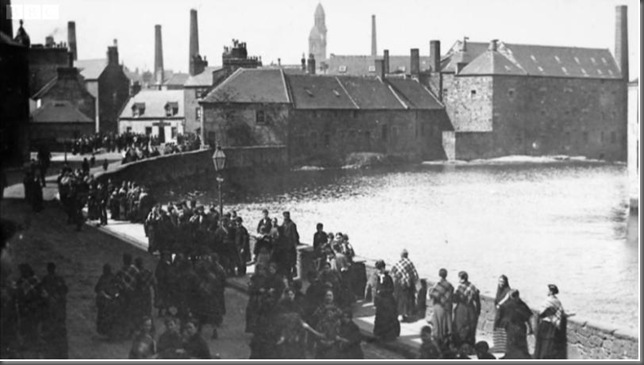

He was one among the many BOR – British Other Ranks – soldiers from these isles who served in India, along with the much larger native forces. They bivouacked in Cantonments waiting to be called out on campaign. When he joined, India was the largest and most important of British colonies. The Army acted as a vast Imperial police force, maintaining law and order and British interests in the region. Gibb was one of sixty thousand white soldiers living and working along with Indian army men in garrison towns across the subcontinent.

It was for the most part a fairly uneventful routine. Gibb’s battalion was moved around from station to station: Benares, Bara Gali, Rawalpindi, Changla Gali, Fatehgarh: carrying out peacekeeping duties and training exercises, ready to be called upon when trouble broke out. He was promoted fairly quickly to Lance Corporal soon after his arrival in India.

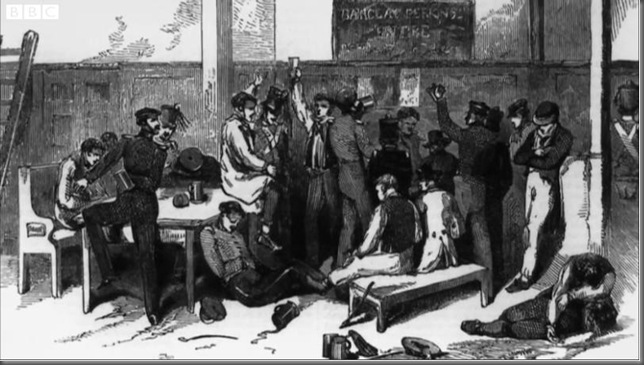

At the time, there were no serious engagements for the Army. There were occasional skirmishes, but in the main, his existence consisted of waking up, parading, facing the odd inspection, guard duties, a never-ending dullness that prompted the bored infractions of military life. For many soldiers there was little to do during the day except go to the wet canteen and drink. And drink they did, hard drinks like rum and arrack. And they gambled, and they lost their money, and they drank more and gambled more in a bottomless spiral.

In Gibb’s case, he was found so drunk that he was hauled up before his commanding officer, sentenced to two weeks’ solitary confinement and reduced in rank. That was the end of his hitherto stellar rise through the ranks, a serious blow to his hopes of bettering his life.

Matthew Gibb was not completely crushed, however, for by the end of that year, he had obtained an Army Certificate of Education, Second Class. This was in recognition of his effort to become literate, having gone to school to educate himself. And then it took him another eight years to regain his rank of Corporal, in 1882. Eventually he ended up being a Staff Sergeant.

This was a man of determination, who had managed to pull himself by his bootstrings to a dignified station in life.

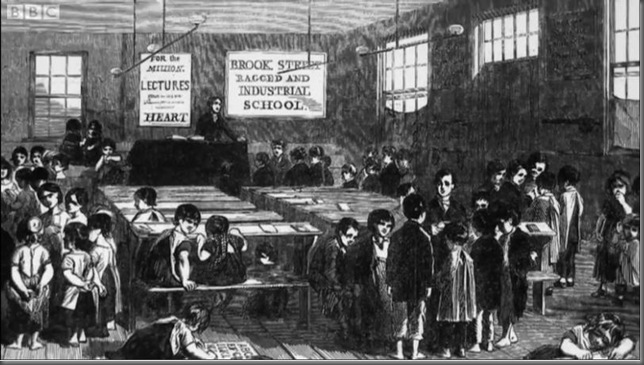

[Matthew Gibb’s early life had been a stark contrast. He was one of several children listed as living in the William Gibb household in the 1851 Census. William was a handloom weaver, a craftsman of that cloth mimicking cashmere that came to be known after the Scottish town of Paisley. But in the 1861 census, Matthew was no longer living with his parents: aged 12, he was in the East Lane Ragged School.

In 1854, Matthew’s mother died; shortly thereafter, William left his children destitute as he went in search of work elsewhere in Scotland. He was away for two years, leaving his children to be cared for by the parish, effectively abandoned. In 1857, Matthew was in the Ragged School; in 1863, his father was institutionalised, driven insane by depression. By the 1870s, the Paisley shawl works were for all purposes extinct, and William Gibb died in a poor-house in 1874.

From BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are? – Robin Gibb.]

5 comments:

Woah. Monster post. So Great-Grandpa was really just stayin' alive? (Yes, it took me an awful long time to come up with that).

There are a few other British rockers whose families served in India (and whose names totally escape me right now, but I'm going to try and dig it up anyway)

Cliff Richard and Engelbert Humperdinck, maybe?

Nah, not those two...more respectable musicians. (apologies to all Cliff Richard and Humperdinck fans)

The mention of the Scottish Rifles in his Military Career is incorrect. I noticed this in the Who Do You Think You Are? episode. The Scottish Rifles (later the Cameronians [Scottish Rifles] ) were made up of the 26th Regiment (Cameronians) & the 90th Regiment (Perthshire Light Infantry - a Rifle Regiment). The 60th is an English Regiment known as the Kings Royal Rifle Corps (a.k.a the Green Jackets), totally different. The KRRC served in Afghanistan, the Scottish Rifles did not. His medal entitlement proves this.

@Anon: Thanks for your comment!

Post a Comment