[I wrote this article on Space Bar's invitation in August 2008 and it appeared on Blogbharti. A little while ago, Blogbharti ceased to exist, my computer crashed, and I thought I'd lost this piece. Luckily, the Wayback Machine had snapped it up all those months ago, and I was able to retrieve it. So here you go, for archival purposes only: this is how it appeared on Blogbharti.]

[ This is Essay No. 31 in our Spotlight Series. Click here for the archives.]

By Fëanor

———-

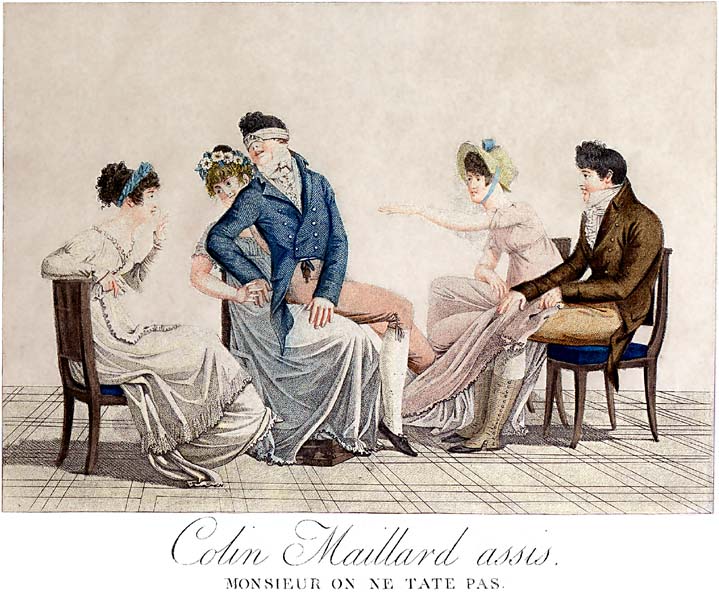

During the height of the Regency, it was the very thing to betake oneself to Brighton, there to enjoy the sea, dance with the best people, flirt with dashing Army officers, be introduced to the Princes Royal, and play genteel parlour games [Picture credit: The Republic of Pemberly]. And when all the whirling and swirling was done and one was exhausted, the place to go to recover and refresh was Mahomed’s.

During the height of the Regency, it was the very thing to betake oneself to Brighton, there to enjoy the sea, dance with the best people, flirt with dashing Army officers, be introduced to the Princes Royal, and play genteel parlour games [Picture credit: The Republic of Pemberly]. And when all the whirling and swirling was done and one was exhausted, the place to go to recover and refresh was Mahomed’s.

To miss going to Mahomed’s is like going to town and forgetting to take a peep at St Paul’s… 1

Inside an imposing building on King’s Road in Brighton, a man in Mughal court dress welcomed the gentry. He offered a luxurious establishment at the height of ton, and a series of medicated vapour baths. The specialty of the house was a massage with medicated oils. Customers sweated their poisons out in a hot aromatic bath, and then moved into a tent with flannel sleeves. Here, an unseen masseur would pummel them invigoratingly, with his arms through the cloth walls. This last, the man said, was the Indian art of the Shampoo, and it would cure all ills.

[The Baths are] daily thronged, not only with the ailing but the hale … their powerful efficacy … have brought foreigners to him from all quarters of the world …

What was this Shampoo? And how did this word become English? The tale is a curious one, intercontinental in its reach, transcending origins, race and class.

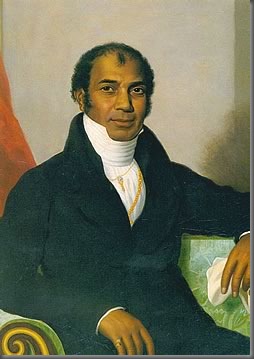

It begins in 1759 in Patna where was born a scion of the Nabobs of Murshidabad. A noble lineage is one thing; the reality of life is another. The Nabobs were a shadow of their former selves after the disaster at Plassey, and Din Mohammed’s father, having set aside all pride, was a minor soldier in the East India Company’s Bengal Army. When Din was eleven years old, his father was killed, his elder brother took on the parental commission, and despite his mother’s vigilance - she knew Din was already smitten by the glamour of soldiery - he ran away from home to become a camp follower. Soon, he was in the service of a Captain Baker, under whose watchful eye he bloomed into a well-read man, widely travelled and keenly observant.

There is scarcely any disease to which the human frame is liable which may not be relieved by the use of these baths.

In 1784, Baker returned to Ireland, taking Din with him. Din perfected his English in Cork, and, after Baker died two years later, married a young Irishwoman, Mary Daly. They spent the next 25 years in Ireland, where Din’s charm and intelligence endeared him to the Irish upper class [Picture credit:Brighton Ourstory].

A popular genre of books at the time was the epistolary travelogue, and Din jumped into the business with panache. The Irish gentry2 paid 2 shillings 6 pence for “The Travels of Dean Mahomet, A Native of Patna in Bengal, Through Several Parts of India, While in the Service of The Honourable The East India Company Written by Himself, In a series of Letters to a Friend.” It was a charming read, in turns poetically descriptive and hair-raisingly adventurous. Interspersed in true intellectual style with quotations from Seneca and Goldsmith, among others, he wrote of the Company’s conquest of India, the gracious Mughals and the elegance of the Company’s Calcutta; he waxed eloquently on the riches of Dacca, and the terrors of being hunted by peasants, wrathful at Din’s tax-collection, baying for his blood.

This unlikely tome turned out to be the first book in English written by an Indian, and it brought to its readers a particular sensibility - an appreciation for victorious England and her East India Company, but also an unapologetic love for the grandeur of India that Din missed so sorely.

You will here behold a generous soil crowned with plenty; the garden beautifully diversified by the gayest flowers diffusing their fragrance into the bosom of the air; and the very bowels of the earth enriched with inestimable mines of gold and diamonds. 3

In 1807, Din and his family moved to London, where he opened an Indian restaurant. The Hindustanee Coffee House in the Portman Estate [Picture credit: BBC News] was the first ever in a series of Indianised British eateries that has continued to this day. While his intention had been to attract the Indian gentry, they tended to look down upon his establishment as one fit only for ignorant Londoners. The British loved it.

Here the gentry may enjoy the Hooakha, with real Chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes in the highest perfection, and allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England.4

Simultaneously, in the service of a Basil Cochrane, he was providing a full body massage service at steam baths opened in Portman Square. Din could easily counter imitators, stating that his was the only genuine massage; only an Indian native could provide a treatment superior to all others; only he, equipped with the correct medicinal herbs, could cure illnesses. In a time of burgeoning excess and a thirst for the exotic, Din was able to provide each in luxuriant quantities.

But setting a trend to be followed by most curry houses after him, Din’s outgoings overwhelmed his income, and he declared bankruptcy in 1812. He let it be known that he was ready for employ as a butler or a valet, with no objection to town or country, and this advertisement brought him to Brighton’s bath houses.

Brighton was the Nonesuch town of the Regency, its wealth and fashion attracting the finest artists and bon viveurs in the land. The Prince Regent’s fanciful Royal Pavilion was then being constructed. The demand for Oriental chic and exotica continued unabated. Din began to purvey esoteric Indian medicines, aromatic herbs and oils, treatments, and promoted steam baths and Shampooing.

shampoo (v.)

1762, “to massage,” from Anglo-Indian shampoo, from Hindi champo, imperative of champna “to press, knead the muscles” 4

The last two became immensely popular; the Prince of Wales invited Din to supervise the construction of an aromatic steam bath in the Pavilion. Din so impressed the Prince that he was anointed Royal Shampoo Surgeon. The gentry poured into his establishment, allowing him to expand, build the elegant Mahomed’s Baths [Picture credit:Victorian Turkish Baths] overlooking the sea, and create new branches in London.

Meanwhile, Din worked on his magnum opus, “Shampooing, or, Benefits Resulting from the Use of the Indian Medicated Vapour Bath,” a book of testimonials from satisfied clients, dealing with the putative medical benefits of massages, aromatic oil therapy and sea-water baths, claiming to cure rheumatism, fix problems of the muscles, and restore ailing joints. His book was a bestseller, going into further editions in 1826 and 1838, adumbrated with fulsome praise from a fawning clientele.

The greatest blessing that we know,

In health is said to be;

That blessing, under God I owe,

Oh Mahomed! to thee;

My lips the gratitude shall show,

That in my heart doth glow,

For ah! I feel too well assured,

(Let all deride, and laugh who will,)

That had I never try’d thy skill,

I never had been cured!!’ 6

The royal warrant by George IV was the final imprimatur on his social eminence, but his financial situation was precarious, dependent as he was on his sleeping partner, Thomas Brown, for funding. Brown died in 1841, and Din was unable to raise the capital required to win the auction of his baths. He offered to manage the property on behalf of the higher bidder, but unfortunately, his services were no longer required, and he had to relocate to a small property on Black Lion Street. He tried to compete with his old establishment, continuing to advertise his services till 1845. He became more and more impecunious in the ensuing years, and in 1851, this extraordinary Renaissance man died.

References:

- Victorian Turkish Baths, Malcolm Shifrin.

- Sake Dean Mahomet: Traveller and Shampooing Surgeon, Niaz Zaman.

- The Travels of Dean Mahomet, Michael Fisher.

- An Indian with a triple first, William Dalrymple, The Spectator, Jan 3, 1998

- shampoo. (n.d.). Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved May 14, 2008, from Dictionary.com: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/shampoo

- Shampooing, Sake Dean Mahomed..

3 comments:

phew. all rescued and all.

phew indeed!

very good ishtyle ji unkelji

xxx

daku khadagsingh

Post a Comment